Ever wondered why your dad or uncle has to rush to the bathroom at night? BPH symptoms can feel like a family curse, but is there a genetic link? This article breaks down what benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) actually is, which signs signal a problem, and how much of that comes from your DNA versus lifestyle choices.

- BPH is a non‑cancerous growth of the prostate that most men face after age 50.

- Common signs include frequent urination, weak stream, and the urge to go at night.

- Family history does raise risk, but hormones, age, and habits play big roles.

- Genetic studies point to several genes that may tip the scale toward enlargement.

- Knowing your risk helps you catch problems early and choose the right management plan.

What is Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia?

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia is a non‑cancerous enlargement of the prostate gland that typically occurs as men age. The prostate surrounds the urethra, so even a modest increase in size can constrict urine flow.

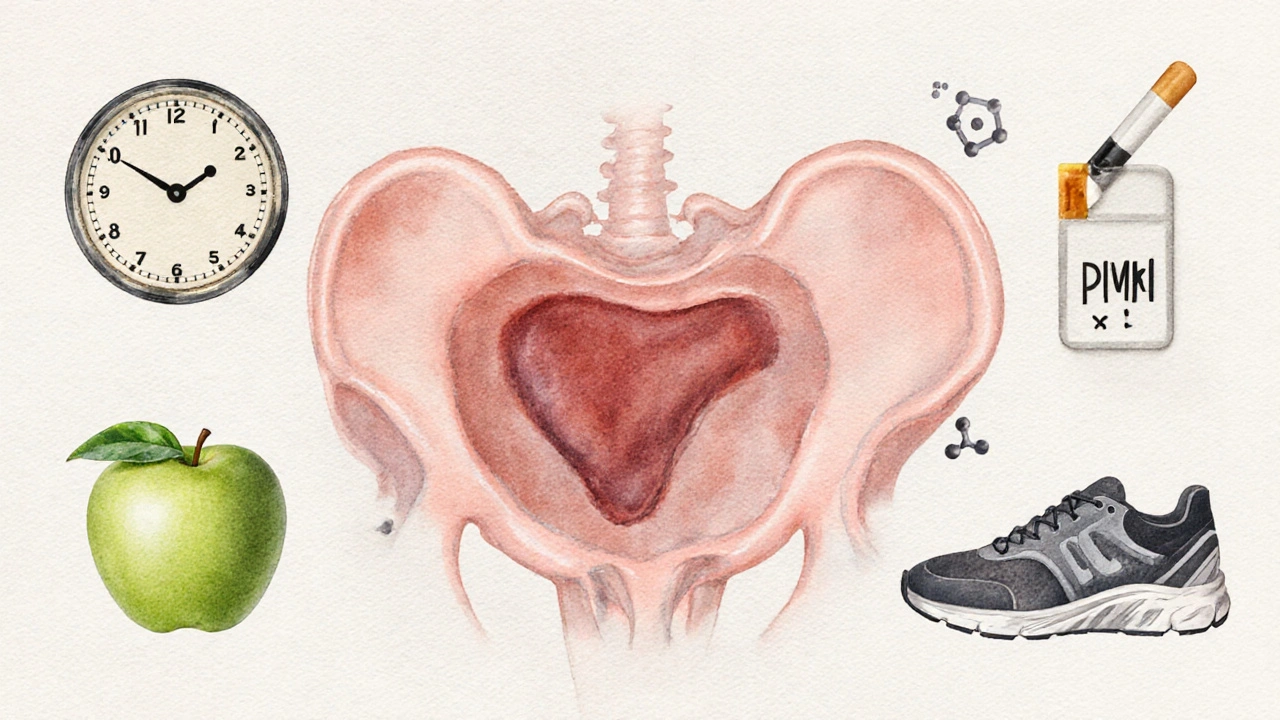

Where does the enlarged prostate sit?

The prostate gland is a small, walnut‑shaped organ located just below the bladder

produces seminal fluid and regulates urine passage. When it swells, the urethra narrows, creating the classic urinary complaints.Typical BPH Symptoms to Watch For

Most men notice one or more of these urinary symptoms such as increased frequency, nocturia, urgency, and a weak stream

. They often develop gradually, but sudden changes merit a doctor’s visit.- Frequent need to urinate, especially at night (nocturia).

- Difficulty starting or stopping the stream.

- Feeling of incomplete bladder emptying.

- Dribbling after finishing.

- Urgent need to go, sometimes with leakage.

These signs are collectively called lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and can affect quality of life as much as the enlargement itself.

Is BPH Hereditary? The Genetic Angle

Research shows a clear hereditary component. Men with a father or brother diagnosed with BPH are up to 2‑3 times more likely to develop the condition themselves. This boost comes from two sources: shared genes and shared environment.

Scientists have identified several genes that influence prostate cell growth and hormone metabolism

, notably SRD5A2 (which encodes the enzyme 5‑alpha‑reductase) and KLK3 (PSA gene). Variants that increase enzyme activity raise levels of dihydrotestosterone a potent androgen that drives prostate tissue growth. Men carrying certain SRD5A2 alleles have an 18% higher risk of moderate‑to‑severe BPH by age 70.Hormones, Age, and the Non‑Genetic Drivers

While genetics set the stage, hormonal shifts and age dominate the plot. Testosterone levels decline with age, but a larger fraction is converted to dihydrotestosterone

inside the prostate. This conversion fuels cell proliferation.Age is the single biggest risk factor: prevalence rises from about 8% in men in their 40s to over 70% after 80. Lifestyle choices-high‑fat diets, sedentary habits, and chronic inflammation-also tip the balance.

Comparing Hereditary vs. Non‑Hereditary Risk Factors

| Factor | Hereditary Influence | Non‑Hereditary Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Family history | 2‑3× higher odds if father/brother affected | None |

| Specific gene variants (SRD5A2, KLK3) | 18‑25% increased risk per risk allele | None |

| Age | Minor (older carriers have higher expression) | Prevalence climbs sharply after 50 |

| Hormonal environment (DHT levels) | Genetic predisposition to higher 5‑alpha‑reductase activity | Diet, obesity, medications affect DHT |

| Lifestyle (diet, exercise) | Limited direct link | High‑fat diets, low activity raise risk |

Assessing Your Personal Hereditary Risk

Start with a simple family tree. Note any male relatives diagnosed with BPH, prostate enlargement, or even prostate cancer, as overlapping risk pathways exist. If two or more first‑degree relatives have BPH, consider an earlier screening schedule.

Doctors may order a prostate‑specific antigen (PSA) blood test and a digital rectal exam (DRE) starting at age 45 for those with a strong family history, versus the usual 50‑year threshold.

Genetic testing for the SRD5A2 variant is available through specialized labs, but it’s rarely necessary unless you have a compelling family pattern and want tailored prevention strategies.

Managing BPH No Matter the Cause

Whether the issue is inherited or lifestyle‑driven, the treatment ladder looks similar. First‑line approaches focus on lifestyle tweaks:

- Limit caffeine and alcohol, which irritate the bladder.

- Stay active - regular walking can reduce inflammation.

- Maintain a healthy weight; excess fat raises DHT levels.

- Practice timed voiding: gradually increase intervals between bathroom trips.

If symptoms persist, medications come into play. Alpha‑blockers relax smooth muscle in the prostate and bladder neck, improving urine flow

(e.g., tamsulosin) work quickly. 5‑alpha‑reductase inhibitors shrink the gland over months by lowering DHT production (e.g., finasteride) are especially useful for men with a strong genetic predisposition.In severe cases, minimally invasive procedures or surgery (like transurethral resection) may be needed, but these are reserved for when medication fails and quality of life is seriously impacted.

Key Takeaways

Hereditary factors definitely nudge the odds upward, but they’re only part of the story. Age, hormones, and lifestyle choices often dominate the final outcome. Understanding your family history lets you act sooner, but lifestyle adjustments and medical therapy remain the backbone of management.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can BPH be prevented if I have a family history?

You can’t stop the prostate from growing entirely, but adopting a healthy diet, regular exercise, and managing weight can lower the severity of symptoms. Early screening also helps catch problems before they worsen.

At what age should I start getting checked if my dad had BPH?

If a first‑degree relative was diagnosed, begin discussions with your GP at age 45. The doctor may suggest a PSA test and a digital rectal exam to establish a baseline.

Do gene‑tests for BPH exist?

Specific tests for variants like SRD5A2 are offered by some labs, but they’re not routine. Most physicians rely on family history and symptom assessment rather than genetic screening.

Is BPH the same as prostate cancer?

No. BPH is a benign enlargement, while prostate cancer involves malignant cells. However, both can raise PSA levels, so abnormal findings often prompt further testing to rule out cancer.

What’s the difference between alpha‑blockers and 5‑alpha‑reductase inhibitors?

Alpha‑blockers relax the muscle fibers in the prostate and bladder neck, providing quick relief of urinary flow issues. 5‑alpha‑reductase inhibitors lower DHT levels, gradually shrinking the gland over several months. They’re often used together for stronger effect.

diego suarez

September 28, 2025 AT 16:14It’s easy to think that a family history of BPH means the "curse" is set in stone, but the article makes it clear that genetics is only part of the picture. Your dad’s or uncle’s symptoms can be a warning sign, yet lifestyle choices like diet and exercise still play a big role in how severe those symptoms become. So, keep an eye on the early signs and talk to your doctor before the problems get worse.

Brian Lancaster-Mayzure

September 28, 2025 AT 17:14For anyone looking at the hereditary risk, a good first step is to map out male relatives who had BPH. This helps your doctor decide when to start PSA testing or a digital rectal exam. Even if you have the genes, simple changes-like reducing caffeine, staying active, and managing weight-can keep the urinary symptoms at bay.

Erynn Rhode

September 28, 2025 AT 18:20Reading through the genetics section reminded me how often the conversation about BPH skips the nuances of gene‑environment interaction. While the SRD5A2 and KLK3 variants are highlighted as risk alleles, they don’t act in a vacuum; hormonal shifts, diet, and inflammatory processes modulate their expression. It’s fascinating that an 18% rise in risk tied to a single allele can be offset by a low‑fat, high‑fiber diet that lowers systemic inflammation. Moreover, the interplay between 5‑alpha‑reductase activity and circulating testosterone levels suggests that pharmacologic inhibition may be more effective in genetically predisposed men. 😊

On the other hand, the article could have delved deeper into epigenetic mechanisms-like DNA methylation patterns that change with age and lifestyle-which might explain why two brothers with identical genotypes sometimes experience markedly different symptom severity. Also, the table comparing hereditary and non‑hereditary factors is handy, but a visual chart showing age‑related prevalence curves would make the data more accessible. Finally, while PSA testing is recommended earlier for those with a strong family history, it remains controversial because elevated PSA can be driven by BPH itself, leading to potential over‑diagnosis of prostate cancer. In short, understanding your family history is a valuable tool, but it’s just one piece of a multifaceted management plan that includes lifestyle adjustments, regular monitoring, and, when appropriate, medication.

Rhys Black

September 28, 2025 AT 19:20Ah, the age‑old trope of blaming genetics for every ailment-how delightfully simplistic! One would think that in the era of genomics we’d move beyond the melodramatic narrative that your patriarch’s toilet trips are destiny. Instead, the piece responsibly reminds us that hormones, diet, and sheer inertia play starring roles. Still, I can’t resist a dramatic flourish: imagine a world where men, armed with gene‑tests, march into the clinic like knights brandishing their DNA swords, demanding personalized potions. Yet the reality is far less theatrical; it’s about sensible choices, not mythic inevitability.

xie teresa

September 28, 2025 AT 20:20I hear you, Diego and Brian, about the balance between genetics and lifestyle. It can feel overwhelming when family history looms, but remembering that habits like staying active and watching caffeine can actually shift the odds is empowering. Everyone’s story is different, so tailoring a plan with your doctor makes sense.

Srinivasa Kadiyala

September 28, 2025 AT 21:20Honestly, the whole "genetic predisposition" hype is overblown; let’s be real-most men won’t even notice BPH until they’re well into their 60s, and by then lifestyle factors have already dictated the severity-so tying it to a single allele is a classic case of reductionist thinking; moreover, the article glosses over the fact that 5‑alpha‑reductase inhibitors work regardless of genotype, which undermines the claim that genetics is the primary driver.

Alex LaMere

September 28, 2025 AT 22:20Genetics is a factor, not a fatal sentence. 🚫

mitch giezeman

September 28, 2025 AT 23:20Exactly, Alex. While the gene variants add nuance, the core message stays the same: lifestyle tweaks and early screening keep the symptoms in check. It’s all about a balanced approach.

Kelly Gibbs

September 29, 2025 AT 00:20Just a heads‑up: if you’re already dealing with frequent nighttime trips, try limiting fluids after dinner-small change, noticeable difference.

Stephanie Pineda

September 29, 2025 AT 01:20Whoa, the whole "family curse" vibe can sound scary, but honestly, it’s more like a friendly reminder to tune in to your body’s signals. Think of it as a colorful roadmap-genes point the way, but you decide the detours. A dash of exercise, a sprinkle of healthy eats, and you’re already rewriting the story. 🌈

Anne Snyder

September 29, 2025 AT 02:20Let’s keep the momentum going! Stay proactive, gather that family history, and partner with your clinician for a personalized monitoring schedule. Early detection plus lifestyle optimization = better quality of life.