When your liver starts to scar, it’s not just a minor repair job-it’s a slow, silent takeover. Cirrhosis isn’t a single disease. It’s the end result of years of damage, where healthy liver tissue gets replaced by hard, fibrous scar tissue that can’t do the job it was meant to do. By the time most people notice symptoms, the damage is already advanced. But understanding what’s happening inside your liver can make all the difference-between managing the condition and facing life-threatening complications.

What Exactly Is Cirrhosis?

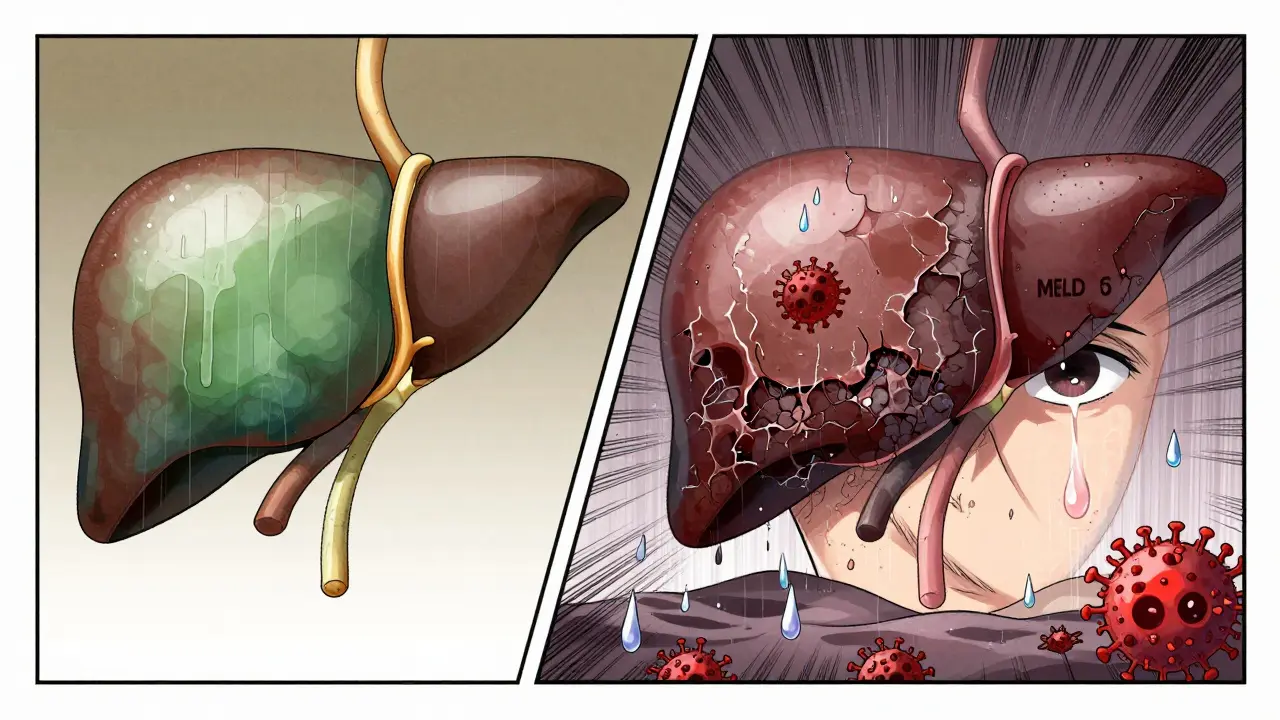

Cirrhosis means your liver has been damaged over and over, and instead of healing properly, it builds up scar tissue. Think of it like a wound that keeps reopening and forming thick, stiff keloids. Over time, these scars wrap around the liver in bands, squeezing blood vessels and blocking the flow of blood and nutrients. The liver, which normally regenerates itself, eventually loses its ability to keep up. The result? A shrunken, lumpy organ that can’t filter toxins, make proteins, or produce bile anymore. The term comes from the Greek word kirrhos, meaning tawny yellow-the color a damaged liver turns. This isn’t just a label; it’s a warning sign that the organ is failing. Unlike fatty liver or early-stage hepatitis, which can sometimes be reversed, cirrhosis is mostly permanent. Once the structure is distorted, the damage can’t be undone. But catching it early-before symptoms show-can still stop it from getting worse.Compensated vs. Decompensated: The Two Stages

Not all cirrhosis is the same. There are two clear stages, and the difference between them changes everything. In compensated cirrhosis, your liver is scarred, but it’s still managing to do the basics. You might feel fine. No swelling, no confusion, no vomiting blood. Blood tests might show slightly high liver enzymes or low platelets, but you’re not in crisis. About 80-90% of people in this stage survive at least five years. Many don’t even know they have it until a routine blood test reveals it. Then comes decompensated cirrhosis. This is when the liver can’t keep up anymore. Fluid builds up in the belly (ascites), the brain gets foggy from toxins (hepatic encephalopathy), veins in the esophagus swell and bleed, and jaundice turns skin and eyes yellow. At this point, survival drops to 20-50% over five years. The body is drowning in its own waste. The shift from compensated to decompensated isn’t random. It’s often triggered by continued alcohol use, uncontrolled hepatitis, or poor diet. It’s also why early diagnosis matters so much. If you catch cirrhosis before symptoms appear, you still have a chance to halt the progression.What Causes It?

Cirrhosis doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s the end of a long road of damage. The biggest causes today are:- Alcohol-related liver disease: Heavy drinking over years slowly destroys liver cells. Even if you quit, scars remain.

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Now the top cause in the U.S., this is linked to obesity, diabetes, and high cholesterol. It starts as fat buildup, then turns to inflammation, then to scar tissue.

- Hepatitis B and C: Chronic viral infections trigger ongoing liver inflammation. Hepatitis C, in particular, can sit silently for decades before cirrhosis shows up.

- Autoimmune hepatitis: Your immune system attacks your own liver.

- Other causes: Genetic conditions like hemochromatosis (too much iron), Wilson’s disease (too much copper), or blocked bile ducts (primary biliary cholangitis).

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t just guess. They piece together clues from blood tests, scans, and sometimes a biopsy.- Blood tests: Look for high bilirubin (jaundice), low albumin (protein shortage), high INR (clotting trouble), and low platelets (spleen enlargement from portal hypertension).

- Imaging: Ultrasound, CT, or MRI can show liver texture changes. Elastography (FibroScan) measures stiffness-values over 12.5 kPa strongly suggest cirrhosis.

- Biopsy: Still the gold standard, but less common now. A tiny sample of liver tissue shows the exact pattern of scarring.

What Happens When the Liver Fails?

When cirrhosis progresses to liver failure, your body starts to shut down in predictable ways:- Ascites: Fluid pools in the abdomen. It’s uncomfortable, makes breathing hard, and can become infected (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

- Hepatic encephalopathy: Toxins like ammonia build up in the blood and reach the brain. You get confused, forgetful, sluggish, or even comatose. Asterixis-flapping hands when arms are outstretched-is a classic sign.

- Variceal bleeding: High pressure in the portal vein forces blood into fragile veins in the esophagus or stomach. These can rupture suddenly, causing vomiting of bright red blood. It’s a medical emergency.

- Jaundice: The liver can’t process bilirubin, so it builds up and yellows your skin and eyes.

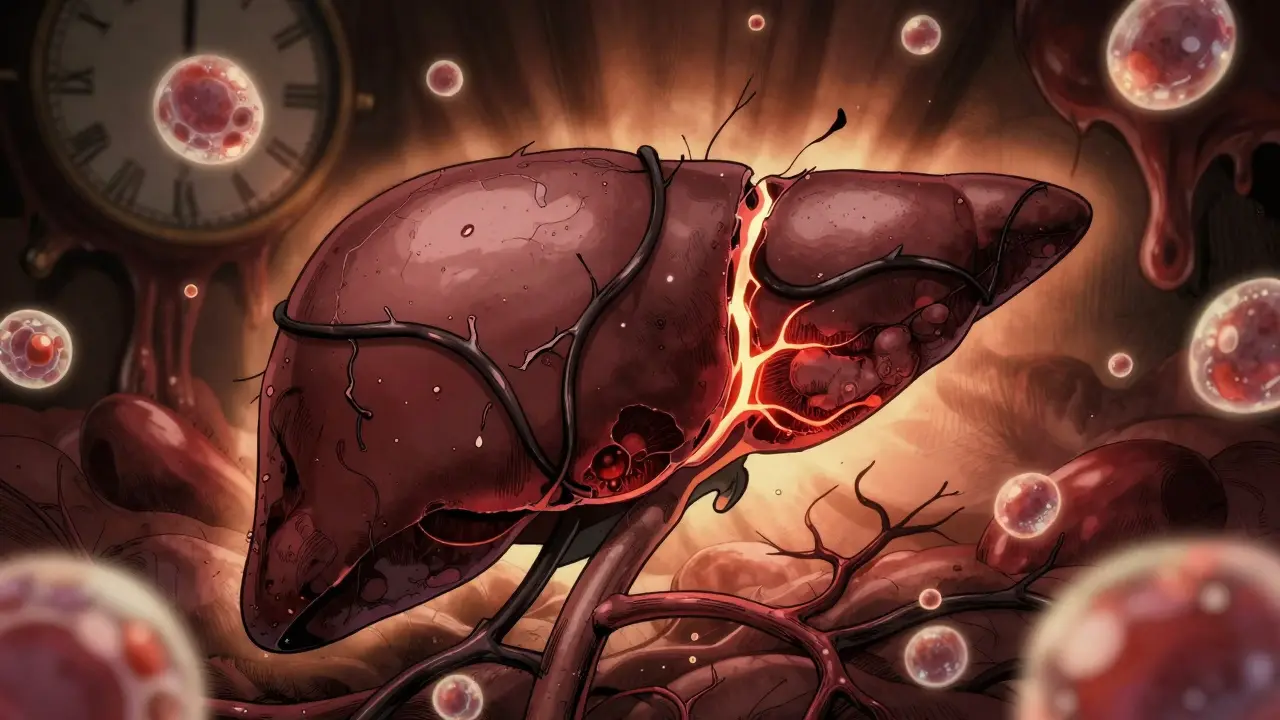

- Liver cancer: Cirrhosis increases your risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by 1-4% per year. Regular ultrasounds every 6 months are standard for monitoring.

Can It Be Reversed?

No medication can undo established cirrhosis. Once the scar tissue is thick and widespread, it’s permanent. But here’s the key: you can stop it from getting worse. If alcohol is the cause, quitting cold turkey can prevent further damage-and in some cases, even improve liver function slightly. For NAFLD, losing 7-10% of body weight can reduce fibrosis. Treating hepatitis C with antivirals can clear the virus and halt progression in over 95% of cases. The goal isn’t reversal-it’s stabilization. If you’re in compensated cirrhosis and you stop the damage, you might live decades without ever needing a transplant. But if you keep drinking, keep eating sugar, or ignore your hepatitis, you’re racing toward decompensation.Liver Transplantation: The Last Option

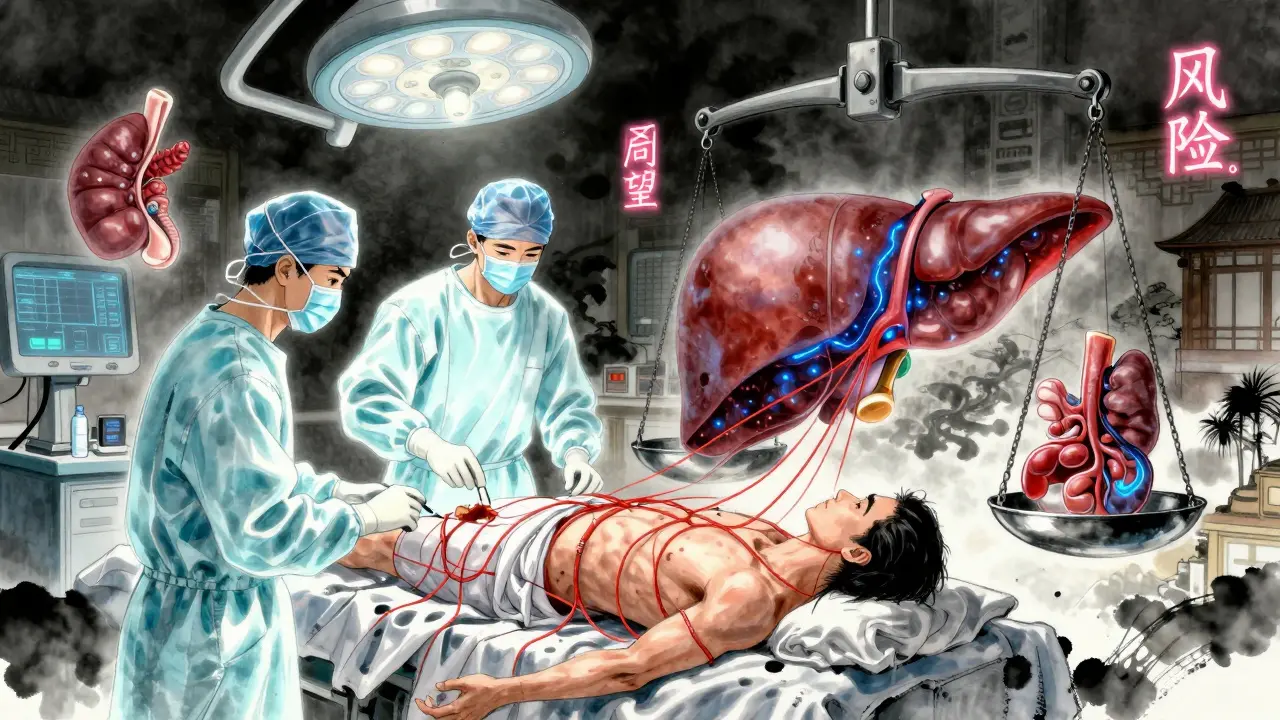

When cirrhosis leads to liver failure, transplant is the only cure. It’s not simple. It’s a major surgery with lifelong consequences. In the U.S., about 8,780 liver transplants were done in 2022. But there were 14,300 people on the waiting list. That means nearly 1 in 10 people die each year waiting for a liver. The MELD score determines who gets priority. The higher your score, the sicker you are, and the higher your chance of getting a liver. Since 2016, the MELD-Na score has been used, which also factors in sodium levels-low sodium means worse prognosis. Transplant success rates are strong: over 80% of patients survive at least five years. But you’ll need to take anti-rejection drugs for life. You’ll need regular checkups. And you’ll need to avoid alcohol, infections, and certain medications. New techniques are helping. Normothermic machine perfusion keeps donor livers alive outside the body, allowing doctors to assess and even repair them before transplant. This has increased the number of usable livers by 22%.

What Can You Do?

If you’ve been diagnosed with cirrhosis-or think you might be at risk-here’s what actually works:- Stop drinking alcohol: Even small amounts can accelerate damage.

- Get vaccinated: For hepatitis A and B if you haven’t been.

- Watch your sodium: Less than 2,000 mg per day to reduce fluid buildup.

- Manage your weight and blood sugar: Especially if you have NAFLD.

- Take only approved medications: Many over-the-counter drugs, including NSAIDs like ibuprofen, are toxic to a cirrhotic liver.

- Get screened for liver cancer: Ultrasound every 6 months.

- Work with a liver specialist: Not just a general doctor. Hepatologists know the nuances.

What’s Next for Cirrhosis Treatment?

Research is moving fast. In 2023, a phase 3 trial showed a new drug, simtuzumab, reduced fibrosis progression by 30% in patients with NASH-related cirrhosis. It’s not a cure, but it’s a step toward slowing the disease. Scientists are also testing bioartificial livers-devices that use living liver cells to filter blood temporarily. And stem cell therapies are being trialed to regenerate damaged tissue. One early trial showed a 40% drop in MELD scores after hepatocyte transplantation. The future may not be just about waiting for a transplant. It could be about stopping cirrhosis before it becomes irreversible.Frequently Asked Questions

Can you live a normal life with cirrhosis?

Yes-if it’s caught early and you follow your doctor’s plan. Many people with compensated cirrhosis live for years without major issues. The key is stopping the damage: no alcohol, healthy diet, regular checkups, and treating the root cause. But once symptoms like fluid buildup or confusion appear, life becomes much more restricted. You’ll need to avoid certain foods, medications, and activities. It’s not a return to "normal," but it can be stable and manageable.

Is cirrhosis the same as liver cancer?

No. Cirrhosis is scarring. Liver cancer is abnormal cell growth. But cirrhosis greatly increases your risk of developing liver cancer. About 1-4% of people with cirrhosis get hepatocellular carcinoma each year. That’s why doctors screen everyone with cirrhosis every six months with an ultrasound and a blood test for AFP (alpha-fetoprotein). Catching cancer early in cirrhotic livers improves survival dramatically.

Can you get cirrhosis without drinking alcohol?

Absolutely. In fact, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now the leading cause of cirrhosis in the U.S. It’s linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and high cholesterol. Even people who never drink can develop severe scarring if their liver is overloaded with fat and inflammation. This is why the term "alcohol-related liver disease" is no longer the default assumption.

How long can you live with decompensated cirrhosis?

Without a transplant, survival drops sharply. About half of people with decompensated cirrhosis live less than two years. The most common causes of death are bleeding, infection, liver failure, or liver cancer. A transplant can extend life significantly-80% of transplant recipients live five years or more. But not everyone qualifies. Age, other health problems, and continued alcohol use can disqualify you.

What are the signs you need a liver transplant?

Your doctor will monitor your MELD score, which predicts your risk of dying within three months. A score above 15 is a strong indicator. Other signs include repeated hospitalizations for ascites or encephalopathy, bleeding from varices that won’t stop, or liver cancer that hasn’t spread beyond the liver. If your quality of life is severely limited by symptoms and you’re otherwise healthy enough for surgery, you’ll be referred for transplant evaluation.

anthony martinez

January 10, 2026 AT 04:18Michael Marchio

January 10, 2026 AT 21:12neeraj maor

January 12, 2026 AT 13:21Ritwik Bose

January 13, 2026 AT 10:50Paul Bear

January 14, 2026 AT 18:43lisa Bajram

January 15, 2026 AT 07:31Jaqueline santos bau

January 17, 2026 AT 02:10Kunal Majumder

January 18, 2026 AT 13:24Aurora Memo

January 19, 2026 AT 05:22chandra tan

January 19, 2026 AT 18:07Dwayne Dickson

January 21, 2026 AT 00:51