When you have diabetes, your kidneys are under constant stress. Over time, high blood sugar damages the tiny filters in your kidneys, causing them to leak protein into your urine. This is called diabetic nephropathy-and it’s the leading cause of kidney failure in people with diabetes. But here’s the good news: we know exactly how to slow it down. The right medications, used correctly, can make a real difference. And it all starts with controlling protein loss and using ACE inhibitors or ARBs the right way.

What Exactly Is Diabetic Nephropathy?

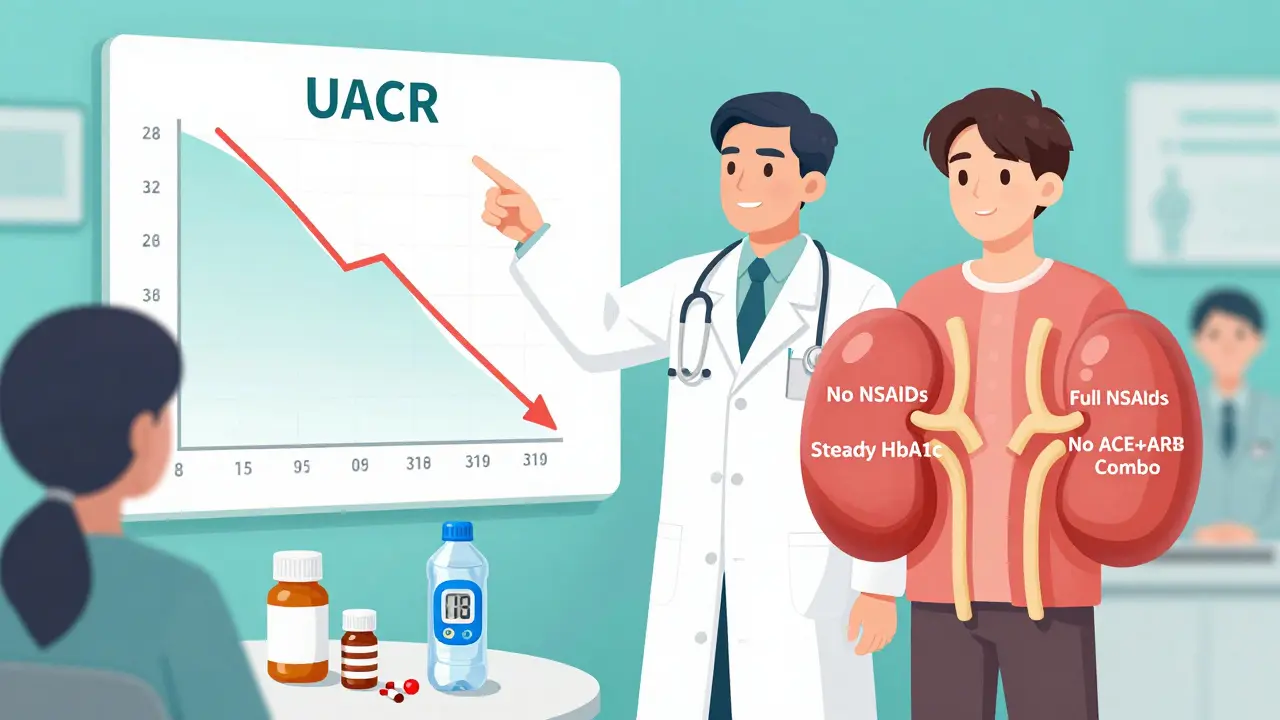

Diabetic nephropathy isn’t just high blood pressure or high sugar-it’s a specific type of kidney damage caused by long-term diabetes. It shows up when your urine starts holding too much albumin, a protein that should stay in your blood. Doctors measure this with a simple urine test called UACR (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio). If it’s above 300 mg/g, you’ve got severely increased albuminuria-the kind that signals real kidney trouble.

This isn’t just about kidney health. People with diabetic nephropathy are far more likely to have heart attacks, strokes, or die from cardiovascular disease. The kidneys and heart are deeply connected. Damage in one often means trouble in the other.

It doesn’t happen overnight. Most people with type 1 diabetes develop signs after 10-15 years. For type 2, it can show up earlier because many people have had undiagnosed high blood sugar for years. But catching it early-before your eGFR (kidney filter rate) drops below 60-gives you the best shot at stopping it.

Why ACE Inhibitors and ARBs Are the First Line of Defense

For over 20 years, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have been the go-to drugs for diabetic nephropathy. Why? Because they do more than lower blood pressure. They protect your kidneys directly.

Both types of drugs block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)-a hormone chain that tightens blood vessels and increases pressure inside the kidney’s filtering units. High pressure crushes the filters, making them leak protein. ACE inhibitors (like ramipril, lisinopril) stop the body from making angiotensin II. ARBs (like losartan, irbesartan) block angiotensin II from even binding to receptors. Either way, the pressure drops. The leaks shrink. The kidneys breathe easier.

Studies like RENAAL and IDNT proved this. In people with type 2 diabetes and heavy proteinuria, ARBs cut the risk of needing dialysis by up to 30%. ACE inhibitors like captopril showed similar results in type 1 diabetes. These aren’t minor benefits-they’re life-changing.

And it’s not just about saving kidneys. These drugs also lower the risk of heart failure and stroke in diabetic patients. That’s why the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2025 guidelines say: if you have diabetes, high blood pressure, and signs of kidney damage, ACE inhibitors or ARBs aren’t just an option-they’re the standard.

How Much Should You Take? Dosing Matters More Than You Think

Here’s where things go wrong in real-world practice. Many doctors start patients on low doses because they’re afraid of side effects. But the science is clear: low doses don’t work.

Take captopril. In trials that showed kidney protection, patients got 25 mg three times a day. That’s 75 mg total. But in clinics, many get 25 mg once a day. That’s not enough. Same with ramipril: the dose used in trials was 10-20 mg daily. Many patients get 5 mg and call it a day.

That’s like taking half a painkiller and wondering why your headache won’t go away.

The ADA says: titrate to the highest tolerated dose. That means if your blood pressure drops a bit, or you feel a little dizzy at first, you don’t stop. You adjust slowly. You drink more water. You don’t quit.

And here’s a critical point: if your creatinine rises by less than 30% after starting the drug, don’t stop it. That’s normal. It means the pressure inside your kidneys is dropping. That’s the goal. Stopping the drug because of this is one of the biggest mistakes in diabetes care.

Doctors who know this see better outcomes. Patients who stay on full doses have slower kidney decline and fewer hospitalizations.

Protein Control: It’s Not Just About Medication

Medications are powerful, but they’re not magic. You still need to manage protein intake.

For decades, doctors told patients with kidney disease to eat as little protein as possible. That idea has changed. Too little protein can lead to muscle loss, weakness, and worse outcomes. The goal isn’t zero protein-it’s optimal protein.

Current guidelines suggest 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. That’s about 55-60 grams for a 70 kg person. Not a low-protein diet. Not a high-protein diet. Just enough to keep you strong without overloading your kidneys.

Focus on quality: lean meats, eggs, fish, tofu, and low-fat dairy. Avoid processed meats and excessive red meat. And don’t rely on protein shakes or powders unless your dietitian says so. They can spike your protein intake without you realizing it.

Also, keep your blood sugar steady. HbA1c below 7% is the target. Every 1% drop in HbA1c reduces your risk of kidney damage by 20-30%. That’s huge. Combine that with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and you’re stacking the odds in your favor.

Why You Should Never Mix ACE Inhibitors and ARBs

Some patients think: if one is good, two must be better. That’s a dangerous myth.

Trials like VA NEPHRON-D, ONTARGET, and ALTITUDE tested combining ACE inhibitors with ARBs-and found no extra kidney protection. What they did find? A 2-3 times higher risk of high potassium (hyperkalemia) and a doubled chance of sudden kidney failure.

That’s not a trade-off worth making. You’re not getting more protection. You’re just adding risk.

Same goes for adding direct renin inhibitors like aliskiren. No benefit. More side effects.

Stick to one. Pick the one you tolerate best. If you get a cough from an ACE inhibitor, switch to an ARB. If you get dizziness, adjust the dose. But don’t stack them.

What About Other Drugs? SGLT2 Inhibitors, MRAs, and More

There’s new hope. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) and nonsteroidal MRAs (like finerenone) have shown strong kidney and heart benefits in recent trials.

But here’s the catch: every major trial tested these drugs in patients who were already on full-dose ACE inhibitors or ARBs. That means these new drugs are add-ons-not replacements.

If you’re not on an ACE inhibitor or ARB yet, start there. Once you’re on the right dose, then talk to your doctor about whether an SGLT2 inhibitor or finerenone might help too.

And don’t forget about diuretics, calcium channel blockers, or beta blockers. They’re fine to use-but only after you’ve optimized your RAAS blocker. They help with blood pressure, but they don’t protect your kidneys the same way.

What to Avoid: NSAIDs, Diuretics, and Other Risks

Many people with diabetes also take ibuprofen or naproxen for joint pain. Bad idea.

NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) reduce blood flow to the kidneys. When you’re already on an ACE inhibitor or ARB, this combo can cause sudden, serious kidney injury. Even a few days of NSAID use can push you into acute kidney failure.

Same with loop diuretics like furosemide (Lasix). They’re useful for swelling, but they increase the risk of dehydration and kidney stress when combined with RAAS blockers. Use them only if absolutely necessary-and monitor your creatinine closely.

And skip herbal supplements like licorice root or St. John’s wort. They can interfere with potassium levels and blood pressure control. Stick to what’s proven.

Why So Many Patients Still Don’t Get the Right Treatment

Despite decades of evidence, only about 60-70% of people with diabetic nephropathy get an ACE inhibitor or ARB at the right dose. Why?

Doctors worry about creatinine spikes. Patients get scared by side effects. Pharmacies don’t refill because the doctor didn’t specify the dose. Insurance pushes for cheaper alternatives.

The result? Thousands of people are slowly losing kidney function because they’re on half a dose-or no dose at all.

It’s not just about prescribing. It’s about following up. Checking urine protein every 3-6 months. Watching creatinine trends. Talking about side effects. Adjusting doses slowly and confidently.

If your doctor hasn’t checked your UACR in over a year, ask why. If your ACE inhibitor dose hasn’t changed since you started, ask if it’s at the maximum tolerated level. You have the right to ask these questions.

The Bottom Line: Protect Your Kidneys Now

Diabetic nephropathy doesn’t have to lead to dialysis. You have powerful tools: ACE inhibitors, ARBs, smart protein intake, and tight blood sugar control. Use them fully. Use them together. Don’t settle for half measures.

Start with the right drug. Titrate to the right dose. Avoid dangerous combos. Monitor your numbers. Stay strong.

Your kidneys are working hard for you. Give them the protection they deserve.

Can ACE inhibitors or ARBs prevent diabetic nephropathy if I don’t have protein in my urine yet?

No. Current guidelines, including those from the NIH and ADA, do not recommend starting ACE inhibitors or ARBs for primary prevention in people with diabetes who have normal blood pressure and no protein in their urine. Studies show no benefit in slowing kidney damage in this group. These drugs are meant for those who already show signs of kidney stress-like albuminuria or high blood pressure. Taking them unnecessarily doesn’t help and could cause side effects like low blood pressure or high potassium.

What should I do if my creatinine goes up after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB?

If your creatinine rises by less than 30% and you’re not dehydrated, keep taking the medication. This is a normal, expected effect. The drug is lowering pressure inside your kidney’s filters, which reduces protein loss-and that’s exactly what you want. Stopping the drug because of this rise is one of the most common mistakes in diabetes care. Talk to your doctor, stay hydrated, and recheck your labs in 1-2 weeks. If the rise is over 30% or you feel dizzy, weak, or have very low urine output, then contact your provider immediately.

Can I take ibuprofen or naproxen while on an ACE inhibitor or ARB?

Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen while on ACE inhibitors or ARBs. This combination can sharply reduce blood flow to your kidneys and cause sudden kidney injury-even in people who’ve been on these drugs for years. Use acetaminophen (paracetamol) for pain instead. If you must use an NSAID for a short time (like after surgery), make sure you’re well-hydrated and your doctor monitors your kidney function closely. Never take them regularly without medical advice.

Are ARBs better than ACE inhibitors for diabetic nephropathy?

Both are equally effective at protecting the kidneys and reducing proteinuria. The choice usually comes down to side effects. ACE inhibitors can cause a dry, persistent cough in about 10-20% of users. If that happens, switching to an ARB often solves the problem. ARBs don’t cause coughing but may cause dizziness or high potassium. Neither has been proven superior in preventing kidney failure. Pick the one you tolerate better and take it at the highest dose your body can handle.

Do I need to take these drugs for life?

Yes-unless your doctor advises otherwise. Diabetic nephropathy is a chronic condition. Stopping ACE inhibitors or ARBs means your kidney pressure will rise again, and protein leakage will return. Even if your urine protein improves, you still need the drug to keep protecting your kidneys. Think of it like blood pressure medication: you don’t stop because you feel better. You keep going because the disease is still there. Regular check-ups will help your doctor adjust your dose if needed, but stopping isn’t the answer.

Can I use SGLT2 inhibitors instead of ACE inhibitors or ARBs?

SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin are excellent for kidney protection, but they’re not replacements for ACE inhibitors or ARBs. All major studies showing their benefits were done in patients already taking full-dose RAAS blockers. If you can’t tolerate an ACE inhibitor or ARB, your doctor may consider an SGLT2 inhibitor as an alternative-but it’s not the first choice. The gold standard remains an ACE inhibitor or ARB at maximally tolerated dose. SGLT2 inhibitors work best as add-ons, not substitutes.

How often should I get my kidney function checked?

If you have diabetic nephropathy, check your urine protein (UACR) every 3-6 months and your blood creatinine and potassium every 3 months after starting or changing an ACE inhibitor or ARB. Once your dose is stable and your numbers are steady, you can space out tests to every 6 months. But don’t skip them. These tests tell you if your treatment is working-or if something’s going wrong. Early detection saves kidneys.

Jillian Angus

December 24, 2025 AT 06:02Spencer Garcia

December 26, 2025 AT 05:13Raja P

December 26, 2025 AT 22:34EMMANUEL EMEKAOGBOR

December 27, 2025 AT 13:10suhani mathur

December 27, 2025 AT 14:42siddharth tiwari

December 29, 2025 AT 06:16Ademola Madehin

December 30, 2025 AT 05:05Austin LeBlanc

December 30, 2025 AT 07:15niharika hardikar

December 31, 2025 AT 04:12