Air Pollution & TB Risk Calculator

This calculator estimates your potential risk of developing active tuberculosis based on exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the air. Enter your approximate PM2.5 level and other risk factors below to get personalized insights.

Tuberculosis isn’t just a disease you catch from a cough - the air you breathe can make you far more vulnerable. In today’s world, smog, dust, and indoor fumes are quietly pushing TB rates higher, especially in crowded cities. This article breaks down the science, shows the latest numbers, and gives you practical steps to protect yourself and your community.

Quick Take

- People exposed to high levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) have a 20‑30% higher chance of developing active TB.

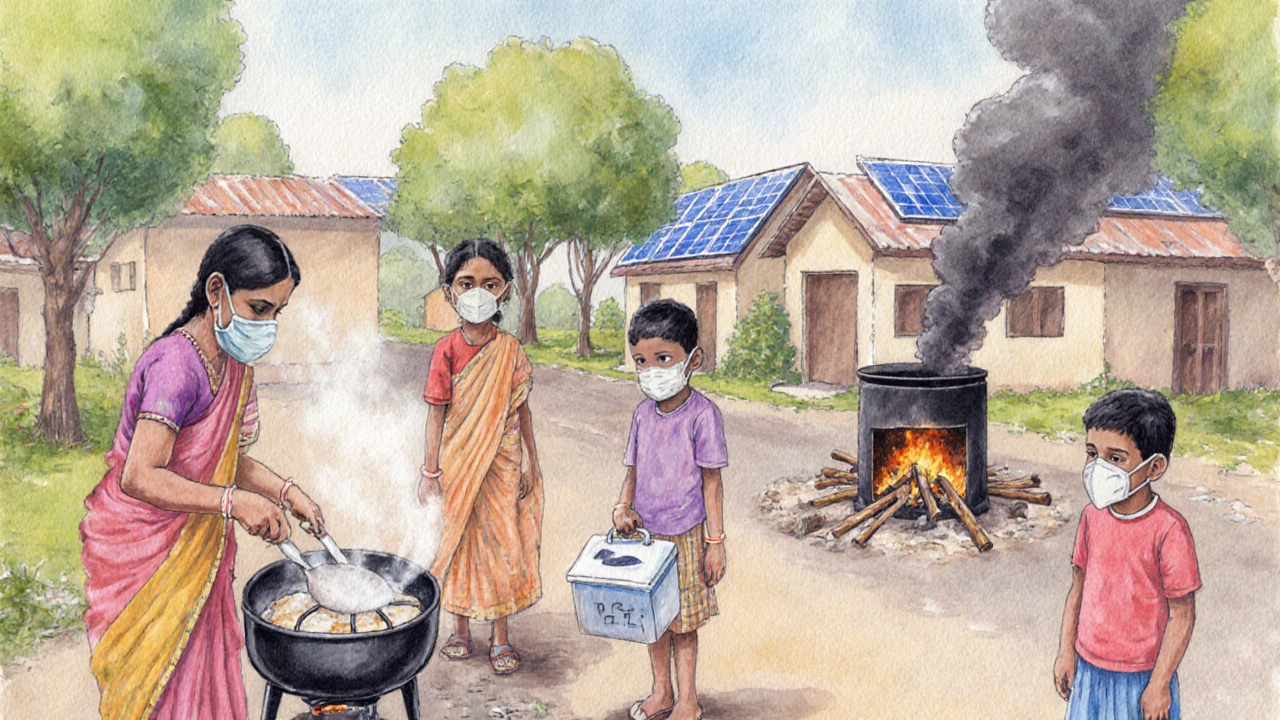

- Both outdoor smog and indoor cooking smoke weaken lung defenses, making infection easier.

- Countries with the worst air quality see the steepest TB incidence spikes, even after accounting for poverty.

- Improving ventilation, using clean fuels, and wearing masks can cut TB risk dramatically.

- Policy actions that lower emissions also lower TB burden - a win‑win for health and the environment.

What Exactly Is Tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacterium that primarily attacks the lungs but can spread to other organs.

When someone inhales the bacteria, the immune system usually walls it off in tiny granulomas. In about 5‑10% of infected people, the bacteria break free, leading to active disease with coughing, fever, and weight loss. Global data from the World Health Organization (WHO) shows roughly 10million new cases and 1.5million deaths each year.

Defining Air Pollution

Air pollution refers to the mixture of harmful substances-like gases, particles, and chemicals-suspended in the atmosphere.

Key culprits include:

- Particulate matter (PM10 and the more dangerous PM2.5)

- Nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) from traffic

- Sulphur dioxide (SO₂) from coal combustion

- Ozone (O₃) formed by sunlight on pollutants

- Indoor smoke from solid fuels (wood, charcoal, dung)

These pollutants irritate lung tissue, drop immune efficiency, and set the stage for infections like TB.

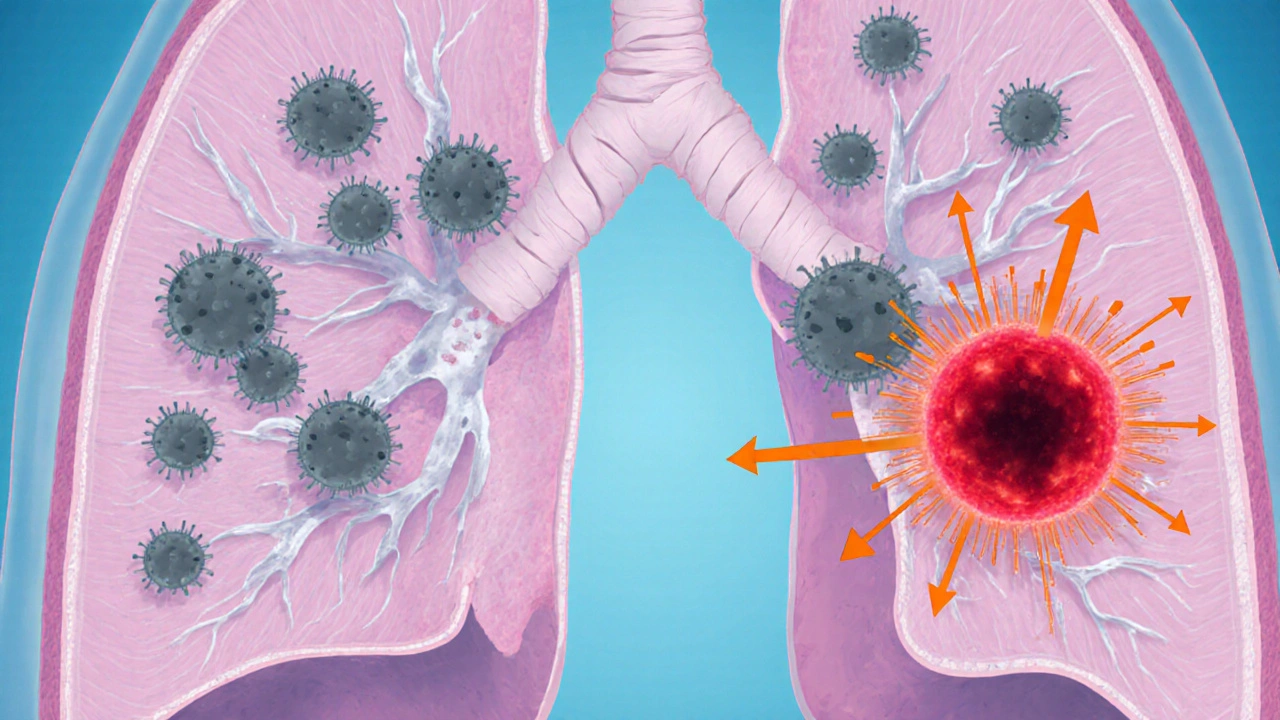

How Pollution Makes the Lungs Friendlier to TB Bacteria

Two main biological pathways link polluted air to higher TB risk:

- Physical damage to airway defenses. Fine particles lodge deep in the alveoli, disrupting cilia (the tiny hairs that sweep microbes out). Studies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show a 40% reduction in ciliary beat frequency after exposure to PM2.5 concentrations above 35µg/m³.

- Immune suppression. Inhaled pollutants trigger chronic inflammation, releasing cytokines like IL‑6 and TNF‑α. Over time, this chronic inflammation exhausts macrophages-the very cells that normally engulf Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lab work from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) found that mice exposed to diesel exhaust had a 2‑fold increase in bacterial load after infection.

Combined, these effects mean that even a brief exposure to smog can tip a latent TB infection into active disease.

Epidemiological Evidence: Numbers That Speak

Large‑scale cohort studies across continents back up the biology:

| Study Region | Pollutant Measured | Average Exposure | Relative TB Risk Increase | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing, China | PM2.5 | 85µg/m³ (annual avg.) | +28% | Chinese CDC 2023 |

| Delhi, India | NO₂ | 70ppb | +22% | WHO Global Air Quality Report 2022 |

| Lagos, Nigeria | Indoor wood smoke | Average 12h/day exposure | +31% | University of Lagos Study 2021 |

| Mexico City, Mexico | O₃ | 60ppb (peak) | +15% | UNEP 2022 |

Across these diverse settings, higher pollution consistently translates into more TB cases, even when researchers control for socioeconomic status, HIV prevalence, and smoking rates.

Who’s Most at Risk?

While anyone breathing polluted air faces elevated risk, certain groups feel the impact hardest:

- Urban dwellers in low‑income neighborhoods. Crowded housing reduces ventilation, and dense traffic spikes outdoor pollutants.

- People who cook with solid fuels. Indoor PM2.5 levels can exceed 500µg/m³ during cooking, dwarfing WHO’s safe limit of 10µg/m³.

- Individuals with compromised immunity. HIV, diabetes, and malnutrition already weaken the immune response, and pollutants add another layer of stress.

- Workers in high‑exposure occupations. Miners, construction workers, and waste‑management staff inhale dust and silica daily.

Practical Steps to Lower Your TB Risk in Polluted Environments

Protecting yourself doesn’t always require a massive infrastructure overhaul. Simple habits can make a huge difference:

- Improve indoor ventilation. Open windows when weather allows, use exhaust fans in kitchens, and install simple air filters (HEPA) in bedrooms.

- Switch to clean cooking fuels. LPG, electric induction, or solar cookers cut indoor PM2.5 by up to 90% compared with wood.

- Use masks on high‑pollution days. N95 respirators filter >95% of particles down to 0.3µm, which includes most PM2.5.

- Get screened regularly. In high‑risk areas, periodic chest X‑rays and sputum tests catch latent TB before it becomes active.

- Support community clean‑energy projects. Grassroots solar and biogas programs have slashed indoor smoke exposure in Kenya and Bangladesh.

Policy Levers: How Governments Can Tackle Both Problems Together

From a macro perspective, health officials and environmental regulators can create powerful synergies:

- Set stricter PM2.5 limits. The WHO revised its guideline to 5µg/m³ in 2024; aligning national standards can immediately reduce exposure.

- Subsidize clean‑fuel transitions. Financial incentives for LPG or electric stoves have led to a 40% drop in indoor smoke in rural Peru.

- Integrate TB screening into air‑quality monitoring programs. Mobile units measuring ambient pollution can also collect sputum samples, cutting costs.

- Promote green urban design. Trees and green walls trap particulate matter, lowering neighborhood-level exposure.

The data shows that every 10µg/m³ reduction in PM2.5 could prevent roughly 50,000 new TB cases globally each year-a tangible public‑health win.

Key Takeaways Checklist

- Know your local air‑quality index and limit outdoor activity when PM2.5 spikes.

- Ventilate indoor spaces, especially kitchens and bedrooms.

- Switch to cleaner fuels wherever possible.

- Wear certified masks (N95/FFP2) on high‑pollution days.

- Get regular TB testing if you live in a polluted or high‑TB‑incidence area.

- Advocate for stricter emissions standards and clean‑energy subsidies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can short‑term exposure to smog trigger active TB?

Short bursts of very high pollution can worsen lung inflammation, but most studies show that long‑term, chronic exposure raises the risk most significantly. However, a single severe smog event can tip a borderline case into active disease.

Is outdoor air pollution more dangerous than indoor cooking smoke?

Both are hazardous, but indoor cooking smoke often reaches much higher concentrations for longer periods, especially in homes without chimneys. In many low‑income regions, indoor exposure is the dominant driver of TB risk.

Do air purifiers actually lower TB risk?

HEPA filters can remove up to 99.97% of particles larger than 0.3µm, which includes most PM2.5. While they don’t replace ventilation, they significantly cut the bacterial load inhaled, thereby reducing the chance of infection progressing.

How does smoking interact with air pollution and TB?

Smoking adds its own set of toxins and further impairs ciliary function. Combined with polluted air, the risk compounds-studies find smokers in high‑pollution zones have up to a 2‑fold higher TB incidence than non‑smokers.

What public‑health programs successfully link air‑quality control to TB reduction?

Chile’s “Clean Air, Healthy Lungs” initiative (2020‑2024) combined stricter vehicle emissions with free community TB screening. The program reported a 15% drop in new TB cases in the pilot cities.

Mary Wrobel

October 3, 2025 AT 16:33Reading about the link between smog and TB really opened my eyes. It’s wild how something invisible can tip the scales toward disease. I’ve always believed the air we breathe shapes our health more than we admit.

Lauren Ulm

October 4, 2025 AT 19:46Ever wonder who’s really pulling the strings behind the "clean air" narrative? 🌫️ The same powers that downplay the pandemic now hush the TB‑air pollution connection. Wake up, folks, before the smoke clears… 🍃

Michael Mendelson

October 6, 2025 AT 00:56Seriously, if you read a single study you’ll see how clueless the mainstream press is. They love to spit out buzzwords like "PM2.5" without any real depth. The average joe never gets the nuance, and that’s exactly why we’re stuck in a cycle of ignorance.

Ibrahim Lawan

October 7, 2025 AT 04:10Air pollution and tuberculosis share a complex, multifaceted relationship that is often overlooked in public health discourse. When fine particulate matter (PM2.5) infiltrates the respiratory tract, it impairs the alveolar macrophages responsible for containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This weakened defense creates a fertile environment for latent infections to reactivate. Moreover, chronic exposure to pollutants induces systemic inflammation, which can dysregulate immune signaling pathways crucial for fighting bacterial pathogens. Studies from high‑pollution regions have consistently reported higher incidence rates of active TB among residents, even after adjusting for socioeconomic variables. The synergistic effect of smoking further compounds risk, as tobacco smoke damages ciliary function and disrupts mucosal barriers. Complementary factors such as indoor use of solid fuels, malnutrition, and HIV co‑infection amplify susceptibility, creating a perfect storm for disease progression. Preventive strategies must therefore be holistic: reducing ambient PM2.5 through stricter emissions standards, promoting clean cooking technologies, and expanding vaccination coverage. Community education campaigns should emphasize not only the respiratory dangers of smog but also its role in facilitating infectious diseases like TB. On an individual level, regular health screenings for at‑risk populations, coupled with nutritional support, can mitigate the compounded threats. Ultimately, tackling air pollution is not just an environmental imperative; it is a vital component of infectious disease control and global health security.

Just Sarah

October 8, 2025 AT 08:46Indeed, the mechanistic pathways you described warrant meticulous scrutiny; however, one must also consider the socioeconomic determinants that intersect with environmental exposures. The interplay between urban planning, healthcare accessibility, and education cannot be understated. Moreover, longitudinal cohort studies are essential to differentiate correlation from causation. Finally, policy implementation should be evidence‑based, integrating multidisciplinary insights.

Anthony Cannon

October 9, 2025 AT 13:23Good summary, thanks for the clarity.

Kristie Barnes

October 10, 2025 AT 15:13I’ve seen the calculator in action, and it’s pretty eye‑opening. It makes the abstract numbers feel personal, which is helpful.

Zen Avendaño

October 11, 2025 AT 19:50Exactly, the data drives home how our daily choices matter. We can all push for cleaner air and better health.

Michelle Guatato

October 13, 2025 AT 00:26Don’t be fooled by the “science” they feed you; the real agenda is to keep us compliant. The link between smog and TB is just the tip of the iceberg! 🌪️ Stay vigilant.

Gabrielle Vézina

October 14, 2025 AT 02:16Honestly, I think the whole narrative is overblown. People love drama, but the data isn’t that shocking.

carl wadsworth

October 15, 2025 AT 06:53Look, I get the drama, but dismissing the risks does a disservice to those suffering.

Neeraj Agarwal

October 16, 2025 AT 11:30Correct grammar matters.