Mycosis Fungoides Diagnostic Pathway Simulator

This interactive tool simulates the diagnostic process for Mycosis Fungoides. Select the clinical features and test results to see how they lead to a diagnosis.

When a persistent rash refuses to respond to ordinary creams, many patients wonder if it could be something deeper than eczema. One rare but serious possibility is Mycosis Fungoides, a type of cutaneous T‑cell lymphoma (CTCL) that starts in the skin and can masquerade as common dermatitis.

Key Takeaways

- Mycosis Fungoides is diagnosed through a combination of clinical observation and several lab‑based tests.

- Skin biopsy, immunohistochemistry, PCR and flow cytometry are the core procedures.

- Staging uses the TNM system and determines treatment intensity.

- Early, accurate diagnosis improves prognosis and opens up skin‑directed therapies.

- Regular follow‑up is essential because the disease can evolve over years.

Below we break down each step, explain what doctors look for, and give you a realistic picture of what to expect during the work‑up.

1. Recognising the Clinical Clues

Before any test is ordered, a dermatologist evaluates the visual pattern of the lesions. Typical signs of Mycosis Fungoides include:

- Flat, scaly patches that appear on sun‑protected areas (hips, buttocks, trunk).

- Progressive thickening into plaques or tumors over months or years.

- Itching that intensifies at night.

- Absence of response to topical steroids or antifungals.

If these features align, the clinician moves to tissue sampling.

2. Skin Biopsy - The Foundation Test

The skin biopsy is the first concrete step. A 4‑mm punch or excisional sample is taken from the most representative lesion, usually an active edge where the skin looks most abnormal.

Pathologists look for three histologic hallmarks:

- Epidermotropism - atypical lymphocytes hugging the epidermis.

- Pautrier microabscesses - tiny collections of malignant cells within the skin.

- Band‑like infiltrate in the upper dermis.

Because early MF can look almost normal under the microscope, further staining is often required.

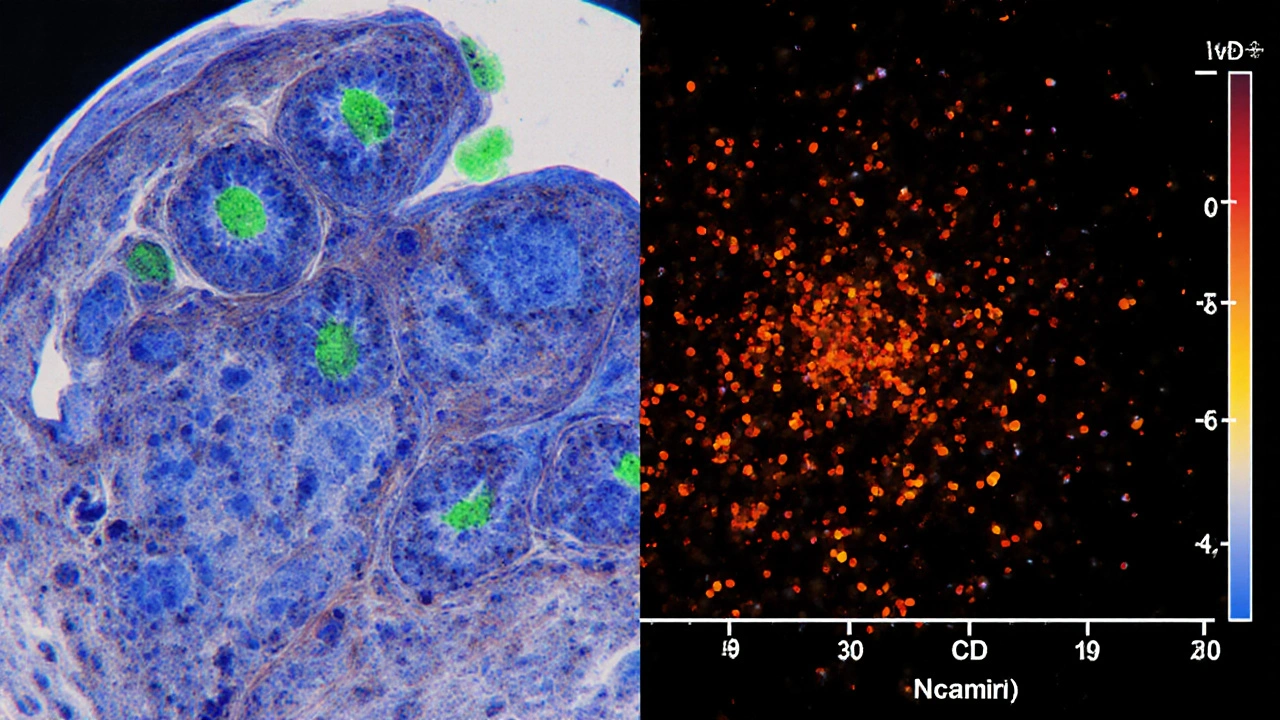

3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) - Tagging the Bad Cells

After the basic H&E slide, the lab runs immunohistochemistry to detect surface markers on the infiltrating T‑cells. The most informative panel includes:

- CD3 - pan‑T‑cell marker (present in both normal and malignant cells).

- CD4 - helper‑T‑cell marker (often over‑expressed in MF).

- CD7 - loss of CD7 is a classic clue for MF.

- CD30 - may be positive in transformed disease.

When the pattern shows CD3⁺/CD4⁺/CD7⁻, the suspicion for MF jumps dramatically.

4. Molecular Tests - PCR and T‑Cell Receptor Clonality

Even with convincing IHC, clinicians often order a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay to detect clonal rearrangements of the T‑cell receptor (TCR) genes. A single dominant clone supports a lymphoma rather than a reactive rash.

Key points about PCR for MF:

- Sensitivity improves with multiple biopsies from different sites.

- A negative result does not rule out MF, especially in early disease.

- Results are usually reported as ‘clonal’, ‘polyclonal’, or ‘equivocal’.

5. Flow Cytometry - Quantifying Aberrant Cells

When blood involvement is suspected, a peripheral‑blood sample undergoes flow cytometry. This technique counts cells expressing atypical marker patterns such as CD4⁺/CD7⁻ or CD4⁺/CD26⁻.

Flow cytometry serves two purposes:

- Detecting early Sézary syndrome, the leukemic counterpart of MF.

- Monitoring disease burden during treatment.

6. Staging the Disease - TNM System

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the next job is staging. The most widely used framework is the TNM system, which captures:

- T - Skin involvement (patches, plaques, tumors).

- N - Lymph node involvement (clinical exam, imaging, biopsy).

- M - Visceral organ spread (CT, PET‑CT).

Stage I disease is limited to patches/plaques (good prognosis). Stage III-IV indicates nodal or visceral spread and typically requires systemic therapy.

7. When to Suspect Sézary Syndrome

Sézary syndrome is the blood‑borne variant of cutaneous T‑cell lymphoma. Typical red‑flag features include:

- Generalised erythroderma covering >80% of body surface.

- Elevated white‑blood‑cell count with >1000 Sézary cells/µL.

- Loss of CD7 and CD26 on circulating CD4⁺ T‑cells (detected by flow cytometry).

Because treatment differs, confirming the syndrome early is crucial.

8. Putting It All Together - A Diagnostic Flowchart

| Test | What it Detects | Typical Sensitivity | When It’s Ordered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin Biopsy (H&E) | Histologic pattern, epidermotropism | ~60% in early disease | First‑line tissue confirmation |

| Immunohistochemistry | CD3, CD4, CD7, CD30 expression | ~80% when combined with biopsy | After ambiguous H&E |

| PCR (TCR clonality) | Clonal T‑cell receptor rearrangement | 70‑90% if multiple sites sampled | When IHC is suggestive but not definitive |

| Flow Cytometry (blood) | Aberrant CD4⁺/CD7⁻ or CD4⁺/CD26⁻ cells | ~85% for Sézary syndrome | If erythroderma or lymphocytosis present |

| Imaging (CT/PET) | Lymph node or visceral involvement | High for stage III‑IV | When clinical exam suggests nodal disease |

9. Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced dermatologists can miss MF. Here are three frequent errors and practical tips:

- Relying on a single biopsy. Early lesions are patchy; obtain at least two samples from different sites.

- Discounting a negative PCR. PCR sensitivity drops if the clone is low‑frequency; repeat testing if suspicion stays high.

- Overlooking blood work. Mild lymphocytosis can be the first sign of Sézary transformation; always add a CBC with differential.

10. Next Steps After a Confirmed Diagnosis

Once mycosis fungoides diagnosis is nailed down, treatment planning begins. Options range from skin‑directed therapies (topical steroids, phototherapy, radiation) for early stages to systemic agents (e.g., oral retinoids, interferon‑alpha, newer biologics) for advanced disease. Regular follow‑up every 3-6months helps catch progression early.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary syndrome?

Mycosis Fungoides primarily affects the skin and progresses slowly. Sézary syndrome is the leukemic form, marked by widespread redness (erythroderma) and circulating malignant T‑cells. Both share the same cell type, but treatment can differ because Sézary involves the blood.

How many biopsies are needed to diagnose early Mycosis Fungoides?

Most experts recommend at least two punch biopsies from separate lesions, especially if the first sample shows only nonspecific dermatitis. Repeating the test improves diagnostic yield to about 80%.

Can a negative PCR rule out Mycosis Fungoides?

No. PCR detects a dominant T‑cell clone, but early disease may have a low‑frequency clone that escapes detection. A negative result should be interpreted with the histology and clinical picture.

Is flow cytometry necessary if my skin looks normal?

Flow cytometry is reserved for cases with blood abnormalities, widespread redness, or when Sézary syndrome is in the differential. If the skin lesions are isolated patches, it’s usually not needed.

What imaging tests are recommended for staging?

A CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis evaluates nodal involvement, while PET‑CT can detect metabolically active disease in skin or internal organs. The choice depends on the clinical stage and physician preference.

Can Mycosis Fungoides be cured?

Early‑stage disease is often long‑lasting but manageable with skin‑directed therapies, and many patients achieve remission. Advanced stages are usually treated to control symptoms rather than cure, though newer targeted drugs are improving outcomes.

Understanding the full diagnostic pathway equips you to ask the right questions at your appointments and to recognise when a referral to a specialty center may be needed. While Mycosis Fungoides is rare, a systematic work‑up dramatically raises the chance of catching it early, when treatment is most effective.

Anna Cappelletti

October 3, 2025 AT 02:50Hey folks, great rundown! The step‑by‑step layout really helps demystify a scary diagnosis. Remember, catching MF early can make a huge difference in outcomes. Keep the optimism alive and lean on your care team.

Dylan Mitchell

October 7, 2025 AT 04:03Oh my gosh this whole MF thing is like a horror movie plot twist!!!

Elle Trent

October 11, 2025 AT 05:16From a diagnostic algorithm perspective, the integration of histopathology with immunophenotypic profiling constitutes the gold standard. Early lesions often manifest with an epidermotropic infiltrate lacking overt cytologic atypia, which necessitates ancillary IHC panels. The CD3⁺/CD4⁺/CD7⁻ signature, while not pathognomonic, significantly raises pre‑test probability. Moreover, clonality assessment via PCR provides molecular corroboration, especially when morphological features are equivocal. In practice, a multidisciplinary tumor board review accelerates time to definitive therapy.

Jessica Gentle

October 15, 2025 AT 06:30Thanks for the comprehensive breakdown, Elle. I’d like to expand on a few practical pearls that often get lost in the literature. First, when you’re scheduling biopsies, aim for the active edge of a plaque rather than an old scar; this maximizes the yield of atypical epidermotropic lymphocytes. Second, always request a concurrent immunohistochemistry panel that includes CD3, CD4, CD7, and CD30, because the loss of CD7 is a subtle but powerful clue. Third, if the initial H&E slide looks bland, ask the pathologist to perform a deep section; many early MF cases hide the diagnostic cells in the dermal‑epidermal junction. Fourth, consider repeating the PCR on a second specimen if the first result is equivocal – clonal peaks can be missed on low‑volume samples. Fifth, peripheral blood flow cytometry isn’t mandatory for every patient, but it becomes essential when you see erythroderma or unexplained lymphocytosis. Sixth, remember that Sézary cells in the blood are defined by a CD4⁺/CD7⁻ phenotype and a count exceeding 1000/µL; this shifts management toward systemic therapy. Seventh, imaging such as PET‑CT should be reserved for stage III‑IV disease, as earlier stages rarely have visceral involvement. Eighth, patient education is key: many individuals mistake MF for eczema and self‑treat with over‑the‑counter steroids, delaying diagnosis. Ninth, longitudinal monitoring every 3–6 months with skin photography can objectively track lesion evolution. Tenth, multidisciplinary collaboration with oncology, dermatology, and pathology streamlines staging and therapeutic decisions. Eleventh, emerging targeted agents like mogamulizumab show promise for CD26‑negative disease and can be discussed early in advanced cases. Twelfth, always document the exact anatomical site of each biopsy to correlate with future imaging findings. Thirteenth, be aware of treatment‑related immunosuppression that can mask disease progression. Fourteenth, maintain a low threshold for re‑biopsy if lesions change morphology or distribution. Finally, a supportive care plan that addresses pruritus, psychosocial stress, and quality of life can markedly improve patient outcomes.

Samson Tobias

October 19, 2025 AT 07:43I completely understand how unsettling a persistent rash can be; it’s normal to feel anxious when the usual creams don’t work. The diagnostic pathway you’ve outlined provides a clear roadmap for both patients and clinicians. Early involvement of a dermatologist can streamline the biopsy process and prevent unnecessary delays. Moreover, having a structured staging system helps set realistic expectations for treatment. Stay proactive and keep open communication with your care team.

Alan Larkin

October 23, 2025 AT 08:56Samson, you’re spot on – the key is early referral. 🧐 In my experience, even a single well‑placed punch biopsy can swing the odds in favor of a timely diagnosis. Just make sure the pathology lab is equipped for immunophenotyping; otherwise you might end up chasing shadows. Also, a quick CBC can reveal hidden lymphocytosis that tips you toward flow cytometry. Bottom line: the sooner you cascade the tests, the sooner you can tailor therapy.

John Chapman

October 27, 2025 AT 09:10Let’s be frank: the literature is replete with studies that demonstrate the superiority of combined histologic and molecular diagnostics over any single modality. Ignoring the PCR data while relying solely on H&E is tantamount to academic negligence. Clinicians who eschew a comprehensive panel are essentially practicing medicine in the dark.

Tiarna Mitchell-Heath

October 31, 2025 AT 10:23John, your sanctimonious tone does nothing for patients battling a relentless disease. The reality is that many community dermatologists lack access to high‑end molecular labs, forcing them to make do with what they have. Throwing shade doesn’t bridge that gap.

Katie Jenkins

November 4, 2025 AT 11:36The diagnostic algorithm you’ve posted is mostly accurate, but there are a few grammatical oversights that could confuse readers. For instance, “Pautrier microabscesses” should be capitalized consistently, and “PCR detects clonal T‑cell receptor rearrangement” needs a hyphen after “T”. Additionally, the phrase “skin‑directed therapies” is more precise than the generic “skin directed therapies”. Minor edits like these improve clarity without altering the scientific content.

Jack Marsh

November 8, 2025 AT 12:50Katie, while I appreciate the attention to detail, stressing minutiae over clinical urgency may distract from the core message. In practice, a clinician’s primary concern is whether the test will change management, not whether the hyphen is perfectly placed. Thus, we must balance linguistic perfection with actionable insight.

Terry Lim

November 12, 2025 AT 14:03If you’re not getting a solid biopsy, you’re basically wasting time.

Mike Brindisi

November 16, 2025 AT 15:16Terry you’re right but sometimes the tissue just won’t cooperate especially in early MF which is notoriously subtle so repeat biopsies are often needed and don’t forget to ask for deeper sections as well

Steven Waller

November 20, 2025 AT 16:30Reflecting on the journey from a simple rash to a complex lymphoma reminds us that medicine is as much an art as it is a science. Each diagnostic step is a brushstroke on the canvas of patient care, and the collective expertise of the team completes the masterpiece. By embracing both empirical data and compassionate listening, we honor the lived experience of those we serve.

Puspendra Dubey

November 24, 2025 AT 17:43Steven, that’s beautifully said – it’s like watching a dramatic plot unfold where the hero (the patient) battles unseen forces and the supporting cast (doctors, labs) rally together to reveal the truth 😱