When a doctor prescribes a generic medication, most patients assume it’s just as safe and effective as the brand-name version. After all, the FDA says so. But behind the scenes, a growing number of clinicians are asking hard questions-especially when the pill they’re handing out comes from a factory halfway across the world. The truth is, not all generics are created equal. And for some drugs, the difference in manufacturing location might mean the difference between healing and harm.

Where your generic drugs really come from

Most people don’t realize that the generic drug in their medicine cabinet could have been made in five different countries before it ever reached the pharmacy. The active ingredient? Probably made in India or China. The inactive fillers? Maybe from Germany. The coating and packaging? Likely done in Mexico or the Philippines. And yet, the label just says "Manufactured for ABC Pharmaceuticals." A 2023 study found that only 14% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in U.S. generics are produced domestically. More than half of the contract manufacturers making these drugs are overseas. That shift didn’t happen overnight-it’s the result of decades of cost-cutting. Generic drug makers, under pressure to offer the lowest price possible, outsourced production to countries where labor and regulatory oversight are cheaper. This isn’t just about geography. It’s about control. When a drug’s components are scattered across continents, there’s no single point of accountability. One facility makes the API. Another blends it. A third puts it in capsules. And none of them are required to disclose their role on the label. If something goes wrong, who do you hold responsible?The hidden cost of cheaper pills

The Ohio State University study from 2023 looked at over 20 million adverse event reports in the FDA’s database. What they found was startling: generic drugs manufactured in India had a 54% higher rate of severe adverse events-like hospitalizations, disabilities, and even deaths-compared to identical drugs made in the U.S. This wasn’t a random outlier. The difference was most pronounced in older, low-cost generics, where profit margins are razor-thin and competition is fierce. "As drugs get cheaper and cheaper and the competition gets more intense to hold down costs," said lead researcher Dr. Robert S. Gray, "it can result in operations and supply chain issues that compromise drug quality." These aren’t just theoretical risks. In 2022, a shortage of a generic blood thinner led to delays in cancer treatments. In 2021, a contaminated generic antibiotic caused a nationwide outbreak of kidney failure. These aren’t rare accidents-they’re symptoms of a system stretched too thin. The FDA insists the U.S. drug supply is safe. And yes, they inspect thousands of facilities every year. But here’s the catch: when they inspect a U.S. plant, they show up unannounced. When they inspect a facility in India or China, they schedule it weeks in advance. That gives manufacturers time to clean up, hide problems, or temporarily boost output to pass inspection.Why bioequivalence isn’t enough

The FDA requires generics to prove they’re "bioequivalent"-meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. On paper, that sounds solid. But bioequivalence doesn’t tell you everything. Think of it like two cars with the same engine size. One might be built with precision German parts and last 200,000 miles. The other uses cheaper materials, has looser tolerances, and starts rattling after 50,000. Both meet the specs on the brochure. But one is far more reliable. In drugs, small differences in how the active ingredient is absorbed, how quickly it dissolves, or how consistently it’s mixed into the tablet can affect how well it works-especially for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure medications. A tiny variation might not show up in a bioequivalence test, but it can trigger a seizure, a stroke, or a dangerous drop in thyroid hormone. Clinicians who’ve seen patients switch from a brand-name drug to a generic-and then have a sudden, unexplained drop in effectiveness-know this isn’t just theory. Many have stopped automatically substituting generics for these critical drugs, even when the law allows it.

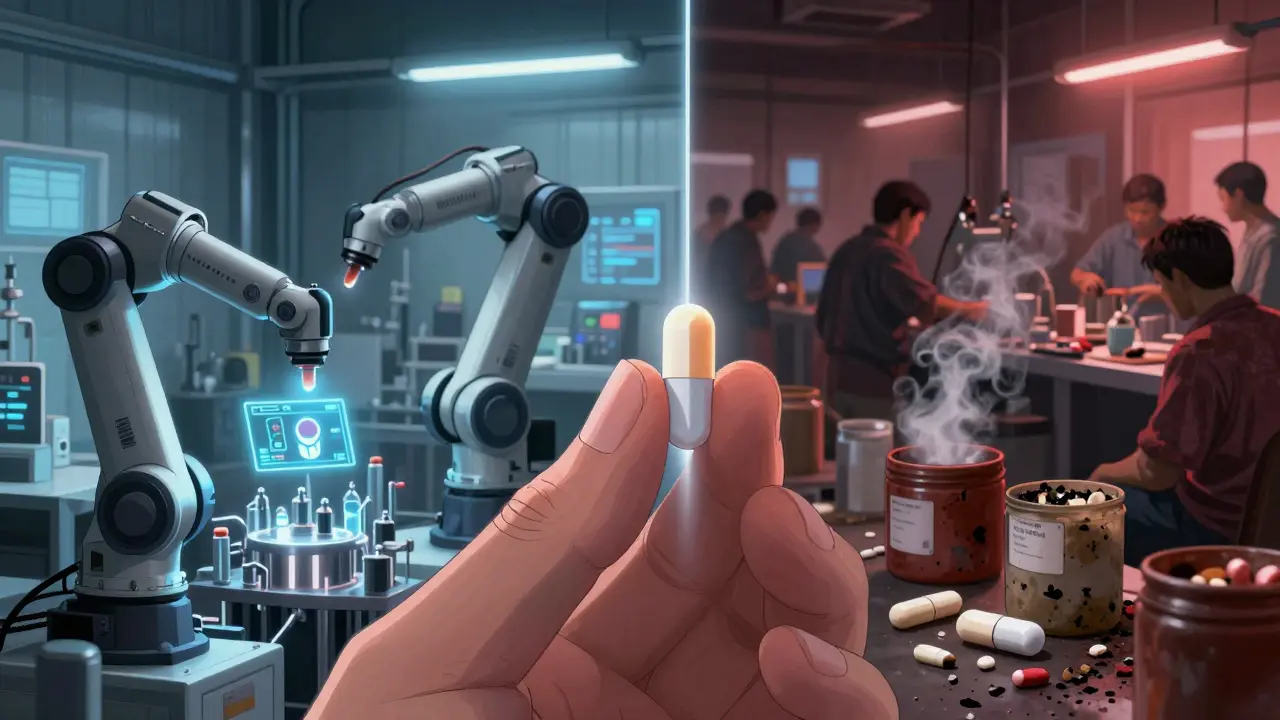

Advanced manufacturing could fix this

There’s a better way. Advanced manufacturing technologies (AMTs)-like continuous manufacturing, real-time monitoring, and automated quality control-are already being used in the U.S. to produce drugs with far greater consistency. Over 80% of drugs made with these technologies are produced domestically. These systems can catch a problem before a single tablet is even packaged. They reduce waste, lower long-term costs, and make it nearly impossible to hide quality issues. But they require big upfront investments. Most generic manufacturers, especially those focused on low-price, high-volume production, can’t-or won’t-pay for them. The Duke-Margolis Center found that once these systems are up and running, they actually reduce per-unit costs. But the industry is stuck in a race to the bottom. Why spend $50 million on a smart factory when you can pay $5 million to a factory in India that’s already got the machinery-and the lack of oversight-to churn out the same pill for less?What clinicians are doing about it

Some doctors are taking matters into their own hands. Instead of accepting the default generic, they’re asking pharmacists: "Where is this made?" If the answer is "I don’t know," they’re switching to a brand-name version-or a generic from a known, reliable supplier. Pharmacists, too, are pushing back. Some hospital pharmacies now track the country of origin for every generic they stock. Others refuse to carry generics from manufacturers with past FDA warning letters. One large health system in the Midwest started requiring manufacturers to provide third-party quality audits before they’ll even consider a new generic product. Dr. Iyer, a clinical pharmacist, puts it bluntly: "Procurers can incentivize quality by ensuring that they only purchase from those who can demonstrate quality assurance and no issues." It’s not about being anti-generic. It’s about being pro-safety. If you’re going to save money by buying a generic, you should be able to trust it. Not hope it works.

The push for transparency

Right now, patients and doctors have no way of knowing where a generic drug was made. That’s changing. Ohio State researchers are calling on the FDA to require labeling that shows the country of manufacture for both the API and the final product. Imagine if every pill bottle had a small print line: "Active ingredient made in India. Final product packaged in Mexico." That kind of transparency would force manufacturers to compete on quality, not just price. It would let hospitals, insurers, and patients make informed choices. And it would give regulators real data to target inspections where they’re needed most. The FDA has resisted this so far, arguing that the current system works. But if the data shows Indian-made generics have a 54% higher risk of severe adverse events, then the system isn’t working-it’s just quiet.Can we fix this without losing affordability?

Yes. But it requires a shift in priorities. The University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy argues that if more generic manufacturing happened in the U.S., we’d have fewer quality concerns, fewer shortages, and a more resilient supply chain. That’s not a pipe dream. The Inflation Reduction Act includes funding to support domestic pharmaceutical production. The FDA is also running pilot programs to help small U.S. manufacturers adopt advanced manufacturing tech. The goal isn’t to bring back every single pill made in America. It’s to reduce our dependence on a handful of overseas factories that are vulnerable to geopolitical shocks, labor strikes, or natural disasters. When a single plant in India shuts down, it can trigger nationwide shortages of life-saving drugs. That’s not efficiency-it’s fragility. The solution isn’t to stop using generics. It’s to stop accepting low quality as the price of low cost. We can have affordable drugs. We can have safe drugs. We just have to stop pretending they’re the same thing.What you can do

If you’re a patient: Ask your pharmacist where your generic medication is made. If they don’t know, ask them to find out. If you’ve had a sudden change in how a generic drug works for you, tell your doctor. Document it. If you’re a clinician: Don’t assume all generics are interchangeable. Know which ones have a history of quality issues. Consider sticking with brand-name for critical drugs if cost allows. Advocate for transparency in your hospital’s formulary. If you’re a policymaker or payer: Demand country-of-origin labeling. Fund domestic manufacturing incentives. Reward manufacturers who use advanced quality controls-not just those who offer the lowest bid. The system isn’t broken because generics are bad. It’s broken because we stopped caring who makes them-and what they’re made of.Are generic drugs less effective than brand-name drugs?

For most people, generic drugs work just as well as brand-name versions. The FDA requires them to meet strict bioequivalence standards. But for certain high-risk medications-like blood thinners, thyroid pills, or seizure drugs-even tiny differences in how the drug is absorbed can matter. Some patients report changes in effectiveness after switching, and clinicians have seen real-world consequences. It’s not that generics are inherently inferior, but quality varies by manufacturer and country of origin.

Why are so many generic drugs made in India and China?

It’s mostly about cost. Labor, regulatory compliance, and facility maintenance are significantly cheaper in countries like India and China. After the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act made it easier to produce generics, companies shifted production overseas to compete on price. Today, over half of the facilities making generic drug ingredients are located in those two countries. While they can produce large volumes cheaply, the trade-off is less oversight and more vulnerability to supply chain disruptions.

Does the FDA inspect foreign drug factories?

Yes, but not the same way they inspect U.S. factories. The FDA conducts unannounced inspections at domestic plants, which helps catch problems in real time. For foreign facilities, inspections are scheduled in advance-sometimes months ahead. This gives manufacturers time to prepare, clean up, or temporarily improve conditions. Experts argue this reduces the chance of catching real quality issues. The FDA says its global inspection program is robust, but data shows higher adverse event rates for drugs made overseas, suggesting gaps remain.

Can I tell if my generic drug is made in a low-quality facility?

Right now, you can’t. Drug labels don’t show where the active ingredient or final product was made. Some pharmacists can look up the manufacturer’s name and check the FDA’s database for warning letters or inspection history, but that’s not easy for most patients. Advocates are pushing for mandatory country-of-origin labeling on all generic drug packaging to give consumers and clinicians better information.

Should I avoid generic drugs altogether?

No. For most medications, generics are safe, effective, and save patients and the system billions of dollars each year. The issue isn’t generics as a category-it’s the lack of transparency and inconsistent quality control across manufacturers. If you’re taking a critical drug with a narrow therapeutic window, talk to your doctor or pharmacist about the manufacturer and where it’s made. Don’t accept a switch without asking questions.

Lethabo Phalafala

January 13, 2026 AT 12:50Let me tell you about my aunt in Johannesburg-she was on warfarin for years, switched to a cheap generic, and started bruising like a grape. No one believed her until her INR spiked to 8.7. Turns out, the batch was made in a factory that skipped stability testing. We’re not talking about ‘maybe’ here-we’re talking about people dying because we outsourced safety for a few cents. This isn’t politics. It’s survival.

And yes, I know generics save money. But when your life depends on a pill dissolving at the exact right speed, ‘saving’ becomes a cruel joke.

We need labels. Not ‘Made in USA’ fluff. REAL labels: API origin, final pack location, batch number. If you’re selling my life, I deserve to know where it was assembled.

Clay .Haeber

January 14, 2026 AT 03:32Oh wow. A 54% higher rate of death? Shocking. Next you’ll tell me the water in India tastes weird. 🤡

Let’s be real-this whole post is just pharma lobbyists in lab coats crying because they lost the price war. The FDA inspects 10,000+ facilities globally. You think they’re asleep? No. You just don’t like that your $0.10 pill isn’t made by some unionized plant in Ohio with a $400k HVAC system.

Also, ‘advanced manufacturing’? That’s just a fancy word for ‘we want you to pay $50 more for the same pill.’

Priyanka Kumari

January 16, 2026 AT 00:43As someone who works in pharma supply chain in India, I see this daily. Yes, cost pressure is brutal. But many Indian manufacturers now have FDA-certified facilities with real-time monitoring. The problem isn’t India-it’s the race to the bottom by U.S. buyers who pick the cheapest bid without asking about quality systems.

We have plants in Hyderabad that produce 100M tablets/month with zero violations. But they’re overlooked because a smaller plant in Bangladesh offers 20% lower price.

Transparency is key. Not blame. If we label origin, we reward the good ones. And yes, we can still keep generics affordable. Just stop rewarding mediocrity.

Milla Masliy

January 17, 2026 AT 05:58I’m a nurse in rural Texas. We switched a bunch of elderly patients to a generic levothyroxine last year. Within months, 12 of them came back with fatigue, weight gain, brain fog. We switched them back to brand-poof. Energy returned in 2 weeks.

It’s not ‘in their head.’ It’s not ‘placebo.’ It’s bioavailability. And no, the FDA’s bioequivalence test doesn’t capture what happens in real bodies over time.

My patients can’t afford brand. But they can’t afford to be sick either. We need a tiered system: cheap generics for antibiotics, premium generics for critical meds. Not all pills are created equal-and pretending they are is medical malpractice.

Damario Brown

January 17, 2026 AT 11:57bro the fda is a joke. they inspected a plant in india and the owner gave them a tour of the clean room while the real production was happening in a garage next door with a guy stirring powder with a stick. i saw the video. the inspector smiled and took a selfie. this isn’t about cost, it’s about corruption. and you know what? i don’t care if your pill comes from china. i care that your doctor doesn’t even know where it’s from. fix that first. also i think we should all just start making our own meds in the basement. 🤷♂️

Adam Vella

January 17, 2026 AT 18:33One must interrogate the epistemological foundations of pharmaceutical equivalence. The FDA’s bioequivalence paradigm is rooted in a reductionist, positivist framework that assumes pharmacokinetic equivalence implies therapeutic equivalence-a flawed axiom, given the non-linear dynamics of human metabolism and the polymorphic nature of excipient interactions.

Moreover, the globalized supply chain is not merely an economic phenomenon but a manifestation of late-capitalist fragmentation, wherein accountability is deliberately dispersed to evade liability. The absence of origin labeling is not bureaucratic oversight-it is structural obfuscation.

One must therefore advocate for a phenomenological approach to drug safety: patient-reported outcomes, longitudinal pharmacovigilance, and mandatory batch-level traceability. Only then can we transcend the illusion of equivalence and confront the ontological uncertainty of the generic pill.

Avneet Singh

January 18, 2026 AT 09:54Oh please. You’re acting like India is some back-alley chem lab. We produce 40% of the world’s generics. Our API plants have ISO 13485, cGMP, and FDA certifications. Your ‘54% higher adverse events’? Correlation ≠ causation. Maybe it’s because your population is obese, diabetic, and on 12 other meds. Or maybe your own domestic supply chain is full of expired stock.

Also, ‘advanced manufacturing’? That’s just automation. We’re automating too. But we’re not going to bankrupt our healthcare system to satisfy your elitist nostalgia for American-made pills.

Stop blaming the Global South for your systemic failures.

Angel Tiestos lopez

January 20, 2026 AT 09:29bro i just took a generic blood pressure pill made in mexico and my head felt like a balloon. i asked my pharmacist and he said ‘oh that’s the one from the new supplier.’ i said ‘which one?’ he said ‘uh… the blue one?’

we need labels. like, actual labels. not ‘manufactured for’ nonsense. i wanna know if my heart medicine was made in a factory where the AC broke last week and the guy who mixed it was high on chai.

also can we just make all critical meds in the usa? i don’t care if it costs $2 more. i’d rather pay $2 than die because someone saved 17 cents.

❤️

Trevor Whipple

January 21, 2026 AT 09:44stop being dramatic. generics work fine. i’ve been taking them for 15 years. if your pill doesn’t work, you’re probably just lazy or your doctor is bad. the fda says its safe so shut up. also why are you so obsessed with where it’s made? it’s a pill. it’s not a handcrafted espresso. 🤦♂️