Why drug shortages are getting worse - and what’s coming next

It’s not just a bad batch or a factory delay. The drug shortages hitting pharmacies today are symptoms of a deeper, growing crisis. By 2027, experts predict that over 40% of essential medicines - from antibiotics to insulin to heart drugs - could face recurring shortages. This isn’t speculation. It’s the result of supply chains stretched thin by global instability, aging manufacturing plants, and a lack of investment in backup systems. And it’s only going to get harder.

The five forces driving future drug scarcity

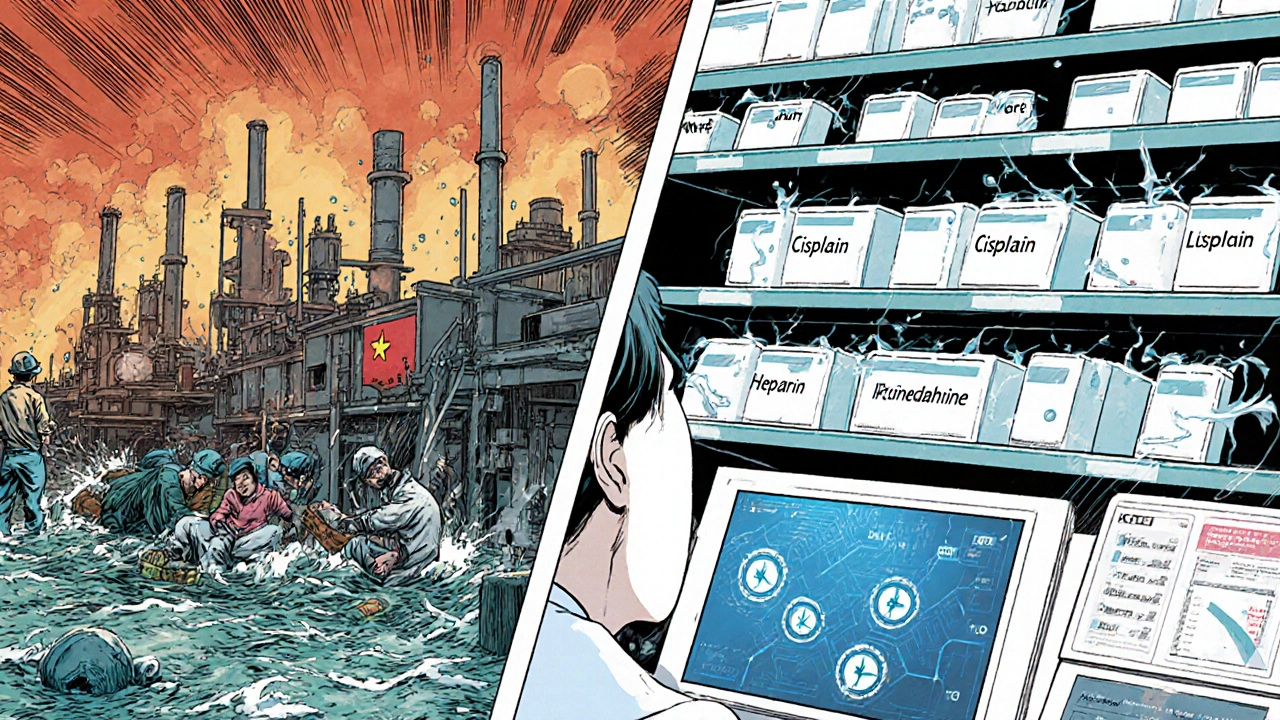

Five big trends are colliding to create perfect storms for drug shortages. First, geopolitical fragmentation is breaking up global supply networks. Over 67% of pharmaceutical companies now rely on raw materials from just two or three countries, mostly in Asia. If trade tensions spike or a port shuts down, entire drug lines can vanish overnight.

Second, manufacturing concentration is a ticking time bomb. Nearly 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for common drugs are made in India and China. One fire at a single facility - like the 2023 shutdown of a major API plant in Hyderabad - can trigger shortages across dozens of countries. There’s little redundancy. No one’s building spare factories.

Third, economic pressure is pushing manufacturers to cut corners. Generic drug makers operate on razor-thin margins. When prices drop due to competition, companies stop producing low-profit drugs - even if they’re lifesaving. Think of injectable antibiotics or chemotherapy agents. These aren’t luxury items. They’re basic care. And they’re vanishing because no one’s making enough money off them.

Fourth, climate-related disruptions are hitting supply chains hard. Droughts in India have reduced water availability for drug manufacturing. Floods in China have halted production of critical compounds. The World Bank estimates that by 2027, climate shocks could disrupt drug production in 12 major sourcing regions - up from just three in 2020.

Fifth, labor shortages in manufacturing and quality control are slowing output. Skilled technicians who test drug purity are retiring faster than they’re replaced. Training new staff takes years. Meanwhile, regulatory agencies like the FDA are understaffed, causing delays in inspections and approvals. A drug that used to get approved in 18 months now takes 28 - and that’s if it’s lucky.

Which drugs are most at risk?

Not all drugs are equally vulnerable. The ones most likely to disappear are:

- Generic injectables - like vancomycin, heparin, and dobutamine. These are cheap to make but expensive to regulate. Manufacturers avoid them.

- Chemotherapy agents - such as cisplatin and methotrexate. Even small production delays can leave cancer patients without treatment.

- Insulin and other hormones - demand is rising fast as diabetes rates climb, but production capacity hasn’t kept up.

- Antibiotics - especially older ones like ampicillin and cefazolin. Pharma companies don’t invest in them because they’re not profitable.

- Emergency drugs - like epinephrine auto-injectors and naloxone. These have short shelf lives and low margins, so they’re often the first to be cut.

According to the FDA’s 2025 Drug Shortage Report, 312 drugs were on shortage in the U.S. alone - up from 178 in 2020. Over half of these have been on the list for over a year. That’s not a glitch. That’s a system failure.

How forecasts are changing - and why they matter

Forecasting drug shortages used to mean watching inventory levels and factory schedules. Today, it’s a complex science. Leading organizations now combine:

- Real-time shipping data from ports and airports

- Climate models predicting droughts and floods in manufacturing regions

- Trade policy alerts from governments

- Supplier financial health scores

- Historical shortage patterns

Companies like IQVIA and Redwood Analytics use AI to analyze these inputs and predict which drugs will run out - and when. Their models now flag risks up to 18 months in advance. That’s a game-changer. Hospitals can stockpile. Pharmacies can find alternatives. Patients can be warned.

But here’s the catch: most hospitals and clinics still don’t use these tools. They’re stuck with manual spreadsheets and vendor calls. The gap between what’s possible and what’s being done is widening.

What’s being done - and what’s not

The U.S. government passed the Drug Supply Chain Security Act in 2013, requiring traceability. That helped. But it didn’t fix the root problems. In 2024, Congress approved $250 million to incentivize domestic API production. It’s a start - but $250 million is less than what one major pharmaceutical company spends on marketing in a single quarter.

Some states are stepping in. California and New York now require hospitals to report shortages in real time and maintain 90-day stockpiles of critical drugs. These policies are working. In New York, the average duration of a shortage dropped from 11 months to 5 months after the rule changed.

Meanwhile, international efforts are lagging. The WHO has no binding rules on drug stockpiling. The EU has better tracking than the U.S. but still lacks a unified response system. And in low-income countries? They get whatever’s left over.

What patients and providers can do now

You can’t control global supply chains. But you can prepare.

For patients: If you take a drug that’s been on shortage lists - like levothyroxine or metformin - ask your pharmacist about alternatives. Don’t wait until your prescription runs out. Keep a 30-day backup supply if possible. Talk to your doctor about switching to a brand-name version if generics are unreliable. It may cost more, but it’s safer than running out.

For doctors and nurses: Use the FDA’s Drug Shortages Database daily. Bookmark it. Set alerts. Know which drugs are at risk in your region. Build relationships with multiple suppliers. Don’t rely on one distributor. If your hospital doesn’t have a shortage response team, push to create one. It’s not extra work - it’s patient safety.

For pharmacies: Stockpile high-risk drugs. Rotate inventory. Don’t wait for the crisis to hit. Use predictive tools - even free ones like the ASHP Drug Shortage Resource Center. And if you’re out of a drug, communicate clearly. Don’t say, “We don’t have it.” Say, “We’re out of X, but here’s what we can give you today - and here’s when we expect more.”

The future: 2027 to 2030

By 2030, the number of drugs in chronic shortage could double. The World Health Organization estimates that over 500 million people worldwide will face difficulty accessing essential medicines. That’s not a guess. It’s a projection based on current trends.

But it’s not inevitable. If governments invest in diversified manufacturing - not just in the U.S. or Europe, but in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia - we can build resilience. If regulators allow faster approvals for alternative suppliers, shortages will shorten. If we incentivize production of low-margin but critical drugs, manufacturers will return.

The technology to predict and prevent these shortages exists. The data is there. The tools are ready. What’s missing is the will.

Drug shortages aren’t accidents. They’re choices - and they’re getting worse because we keep choosing to ignore them until it’s too late.

Why are generic drugs more likely to be in shortage than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs have much lower profit margins, so manufacturers only produce them if they’re profitable. When prices drop due to competition, companies stop making them - even if they’re essential. Brand-name drugs often have patent protections that keep prices higher, so companies keep producing them. This creates a system where the cheapest drugs - the ones most people rely on - are the first to disappear.

Can we just make more drugs in the U.S. to avoid shortages?

It’s possible, but expensive and slow. Building a new FDA-approved drug manufacturing plant takes 5-7 years and costs over $200 million. Even with government incentives, few companies are willing to take that risk. Plus, the U.S. lacks the skilled workforce and infrastructure to produce all the raw ingredients needed. Domestic production helps, but it’s not a full solution without global diversification.

How do climate change and water shortages affect drug production?

Drug manufacturing uses massive amounts of water - for cleaning, cooling, and chemical processes. In India and China, where most active ingredients are made, droughts are becoming more frequent. In 2023, water shortages forced two major API plants in India to shut down for over three months. That caused global shortages of antibiotics and blood pressure meds. Climate models show this will get worse, especially in regions already under water stress.

Are there any drugs that are unlikely to ever go into shortage?

Yes - but only a few. High-value drugs with strong patent protection, like cancer immunotherapies or rare disease treatments, rarely run out because they’re profitable and closely monitored. Vaccines with government contracts (like flu or COVID shots) also have stable supply chains. But for the vast majority of everyday medications - especially generics - no drug is truly safe from shortage.

What should I do if my medication is on shortage?

Don’t stop taking it. Contact your pharmacist and doctor immediately. Ask if there’s a therapeutically equivalent alternative. If not, check the FDA’s Drug Shortage Database for expected restock dates. Some pharmacies can source from international suppliers (legally) if you’re willing to pay more. Never switch to an unapproved substitute - it could be dangerous. And if you’re on a long-term drug like insulin or thyroid medication, ask your doctor about getting a 90-day supply to avoid running out.

What comes next?

Shortages aren’t going away. They’re becoming the new normal. But they don’t have to be. The tools to fix this exist. The data is clear. The cost of doing nothing - in lives, in suffering, in lost time - is far higher than the cost of fixing it.

It’s time to treat drug supply chains like the critical infrastructure they are - not an afterthought.

Holli Yancey

November 18, 2025 AT 15:42I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years. Last year, my pharmacy went three weeks without it. I had to call five different places. One told me they were 'waiting on a shipment from India'-but then I read the article and realized it’s not just them. It’s everyone. I’m just glad I didn’t run out. But what happens when someone can’t afford to keep calling around? Or doesn’t know how?

Gordon Mcdonough

November 19, 2025 AT 19:44AMERICA IS WEAK!!! WHY ARE WE RELYING ON CHINA AND INDIA FOR OUR LIFE SAVING DRUGS?? WE USED TO MAKE EVERYTHING HERE!! NOW WE’RE A NATION OF WHINERS WHO CAN’T EVEN GET INSULIN BECAUSE SOMEONE IN HYDERABAD HAD A POWER OUTAGE!! WE NEED TO BAN FOREIGN PHARMA AND MAKE EVERYTHING IN THE USA!!

Jessica Healey

November 21, 2025 AT 05:40my mom’s on chemo and they switched her to a different brand last month because the generic was gone for 4 months. she cried. not because it cost more, but because she felt like a burden. like her life was just… negotiable. i hate that we’ve made healthcare this transactional. these aren’t gadgets. these are people’s lives.

Levi Hobbs

November 22, 2025 AT 14:30Just want to add that the FDA’s Drug Shortage Database is actually really good if you use it right. I work in a small clinic and we started checking it every morning. We’ve been able to preemptively switch 3 patients off unstable generics to stable alternatives. It’s not perfect, but it’s something. Also, the ASHP resource center has free alerts-sign up. It takes 2 minutes.

henry mariono

November 24, 2025 AT 07:24I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years. I’ve seen this coming since 2010. The system wasn’t broken-it was designed this way. Profit over people. It’s not about lack of will. It’s about who’s pulling the strings. We’re not powerless, but we’re not in charge.

Sridhar Suvarna

November 25, 2025 AT 05:32As someone from India, I see this daily. Our factories are the backbone of global generics-but we lack clean water, stable power, and trained inspectors. We are not the villains. We are the unsung workers holding up a broken system. If you want change, don’t blame us-invest in us. Build labs here. Train our youth. Make this a partnership, not a dependency.

Joseph Peel

November 26, 2025 AT 07:16There’s a reason insulin costs $100 in the U.S. and $5 in Canada. It’s not about manufacturing-it’s about pricing power. The same drug, same factory, same quality-but one country treats it as a human right, the other as a revenue stream. We can fix shortages, but only if we fix the market first.

Kelsey Robertson

November 27, 2025 AT 13:13Oh please. Everyone’s acting like this is news. We’ve had drug shortages since the 1980s. The real issue? You people think medicine should be free. It’s not. It’s a product. And products get discontinued when they’re not profitable. Stop pretending this is a moral crisis-it’s economics. If you want more insulin, pay more for it. Simple.

Joseph Townsend

November 28, 2025 AT 18:09Imagine if your car’s brake fluid kept vanishing because the factory in Taiwan had a monsoon. You’d freak out. But when your heart medication disappears? You shrug and say ‘oh well.’ We’ve normalized medical fragility. It’s not just a supply chain failure-it’s a spiritual collapse. We’ve forgotten that medicine isn’t a commodity. It’s a covenant.

Bill Machi

November 30, 2025 AT 16:51China and India are stealing our medicine. Our factories are shuttered. Our workers are gone. Our government gave away our pharmaceutical sovereignty for cheap generics. Now we’re begging for insulin like beggars at a feast. We need tariffs. We need bans. We need to rebuild our industry-no excuses. This isn’t about ‘diversification.’ This is about survival.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

December 1, 2025 AT 11:38In South Africa, we wait six months for antiretrovirals. We don’t have AI forecasts. We don’t have stockpile mandates. We have mothers who walk 20 kilometers to a clinic, only to be told, ‘Come back next month.’ The world talks about 2027 projections like they’re distant storms. But here? The storm is already here. And no one’s sending lifeboats.